Negotiating Gender in Contemporary Occultism

Podcast with Manon Hedenborg White (10 December 2018).

Interviewed by Sammy Bishop.

Transcribed by Helen Bradstock.

Audio and transcript available at: Hedenborg_White-_Negotiating_Gender_in_Contemporary_Occultism_1.1

Sammy Bishop (SB): Hello, I’m Sammy Bishop. I’m here at the EASR 2018 Conference in Bern. It’s a very sunny day today. And I am joined by Manon Hedenborg White, from Sǒdetǒrn University, a post-doctoral researcher. So, thank you very much for joining us!

Manon Hedenborg White (MHW): Thank you. It’s great to be here.

SB: Have you enjoyed the conference, so far?

MHW: I have, very much. It’s been a little bit of a short visit for me. But I’ve seen some really interesting papers, on a lot of different topics – none of which have really been in my main area of research. So that’s always a fun thing.

SB: So your main area of research is in occultism, and sex magic as well. So, for the Listeners who aren’t too familiar with the field, could you give us a brief outline of what is occultism and sex magic?

MHW: Yes. Definitely. So, occultism: usually the way I explain this is as a particular branch of the broader field that we usually call Western esotericism. So Western esotericism is a very broad umbrella term that’s usually used to encompass a number of different religious and philosophical phenomena, with their earliest roots in late antiquity, which have blossomed in Europe primarily during the renaissance, and which are still in existence today. And which encompass things such as Hermeticism, The Tarot, Astrology, Ceremonial Magic, Rosicrucianism, Freemasonary – or specific branches of Freemasonry – and so on. So occultism, generally, is characterised as specific forms of modern western esotericism. For instance one of the leading experts in this field, Wouter Hanegraaff, characterises occultism as attempts by esotericists to come terms with a “secularised and disenchanted world”. So it’s . . . esotericism, in the meeting with Social Darwinism, modern science, increased religious pluralism, partly as a result of the loss of hegemony on the part of the major churches . . . . So esotericism in the modern world would often be characterised also by attempts to bring in science-like language and science-like methodologies to the study of supernatural realities.

SB: Very eloquently put, as well! So when did this start becoming more popular in the UK or the US, more generally?

MHW: Yes. There have been various waves of it. But definitely a lot happens from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, when we often talk about something called an occult revival. Now, that terms a little bit problematic, because that sort-of implies that occultism or esotericism was somehow not really around before that, which it definitely was. But, certainly, in the second half of the 19th century there was a very strong wave of interest in various forms of religiosity and spiritual systems of meaning outside of the major religious institutions. So that’s when we have phenomena such as spiritualism gaining loads and loads of interest during this time, becoming a very popularised sort-of esoteric or occult movement. We also have the interest in practical magic pioneered by movements such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and we also of course have the genre of literature on sexual magic, as well. These various occultists writing about how they believe that sexual energy or sexual fluid, sexual techniques could be harnessed for magical purposes.

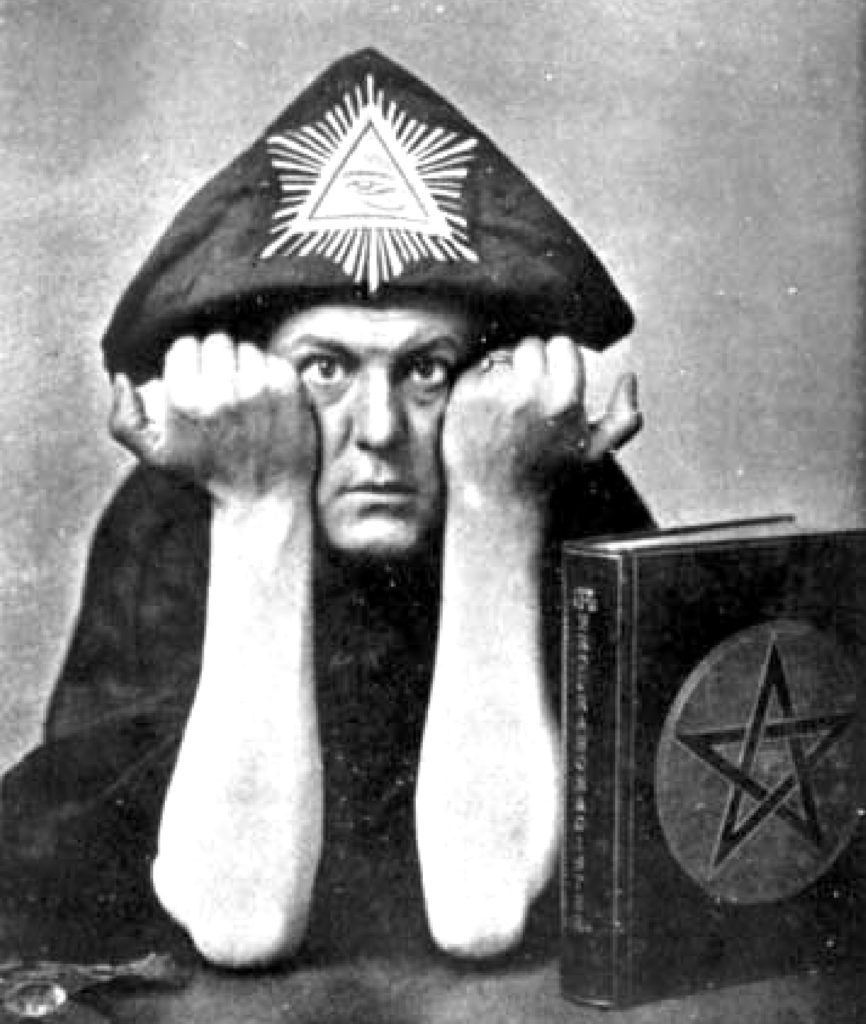

SB: So one of the most popular – well, poplar’s not really the way to put it! One of the most well-known figures within that field was Aleister Crowley. So, could you tell us a bit about it?

SB: Yes. Definitely. So Aleister Crowley is fundamentally one of the most influential occultists of the modern period, basically. He was born in 1875. His parents were members of a conservative Christian Movement – a dispensationalist movement – known as the Plymouth Brethren. And Crowley rebelled against his upbringing at quite a young age. He identified himself very famously as the Great Beast, 666, which is of course a character from the Book of Revelation. And he also brought in, from the Book of Revelation, the Whore of Babylon. Which he reinterpreted as the goddess Babalon representing, among other things, liberated sexuality. So he was really sort of invested in this kind of renegotiation of symbols that within a Christian context were seen as evil or sinister, basically. And this was based on a very sort-of strong critique on Crowley’s part of what he perceived as Victorian and Edwardian and Christian sexual morals. That was one of his strong, strong sort-of . . . . Something that he really focussed on quite a lot was revising Western sexual morals, essentially. So Crowley was drawn into this whole occult trend that was ongoing in England at this time. He joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1898. He left it a few years after that. (5:00) And, in 1904, what happened was Crowley was on honeymoon with his first wife Rose Kelly, in Cairo in Egypt. And he was visited by what Crowley describes as a “discarnate entity”, which he called Aiwass, who dictated to him what would become a sacred text – which was later known as the Book of the Law, or Liber AL vel Legis. This proclaims a new aeon in the spiritual history of humanity, with Crowley as its main prophet and leader, essentially. And the Book of the Law proclaims the very famous maxim: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” And also the word “thelema”, which is Greek for will. So there’s this idea of will as a very important characteristic of this new aeon, which Crowley would later develop into an idea – not so much of doing whatever you want to do in any given moment, but instead something which he called a concept of the True Will. This is the inner hidden unique purpose in each individual life, which is up to each individual man or woman to find and sort-of develop. So that was his main idea and is also the core idea of the religion that Crowley founded, which is known as Thelema.

SB: Thank you. So I understand that a lot of your interests lie in gender aspects, as well. So could you say a bit about how Crowley kind-of explored that, and played with it, and kind-of up-ended it?

MHW: Yes. That’s a really interesting question, and one that I have looked into a lot. And it’s very complex. Crowley is often accused of sexism and misogyny and he does write some things, in some texts, that are quite clearly in that direction, from a contemporary perspective. On the other hand, he was also progressive in some texts. So he often contradicts himself, for instance, in women’s roles. In some texts he writes that women are spiritually sort-of different from men, and have different possibilities for developing, and are generally sort-of spiritually and morally inferior to men. And in other texts he writes more or less the complete opposite. One of his texts from the 1920s . . . . For instance, one of the comments to the Book of the Law is very progressive, actually, even sort-of from a contemporary perspective. He talks about women’s sexual freedom, for instance, and writes that the best women have always been sexually free, and that this is something that is really important. And that was actually quite radical, from the point of view of Crowley’s time. So there’s these massive internal contradictions that you can see as well. Also the sort-of core cosmology, or theology, of Crowley’s religion of Thelema is very strongly gendered. And it’s got all of these gendered symbols that on some levels kind of contradict each other, as well. For instance, within the Book of the Law, there’s a tripartheid cosmology based on the Goddess Nuit, the God Hadit and their divine offspring Ra Hoor Khuit. So there you have the idea of a polarity between masculine and feminine. That’s an interaction with the masculine playing a more active role and the feminine playing a more passive, or receptive, role. Then, on the other hand, you have other deities within the system of Thelema, as well. For instance I was talking earlier about the symbolism of the Beast 666 and the goddess Babalon. The goddess Babalon is seen as one of the most important embodiments of divine femininity within Thelema. And that’s a symbol that is both active and receptive on different levels, you could say. So there’s quite a lot of complexity in that.

SB: So, taking it up to the present day: could you describe who might be involved with contemporary Thelema and how prevalent it is, or where it is, as well?

MHW: Yes. There really is a lack of solid quantitative research on contemporary esotericism overall. So these figures that I’m going to be giving you, are a little bit ball-park. The largest Thelemic organisation in existence today is an organisation known as the Ordo Templi Orientis or OTO, which Crowley led for several years during his lifetime, and which has approximately 4000 members across the globe. About a quarter – slightly more than a quarter of that are in the US. But there are also a couple of hundred members in other countries as well, such as: the UK, Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, large portions of Western and Eastern Europe, some scattered local bodies in Asia, and in Latin America as well. People who tend to be involved are not very different from how people are in general. The research that has been done, and the observations that I have done over the course of my research, say that people within the Thelemic milieu today are: generally a little bit more highly educated than the average population (10:00); maybe slightly more men than women – although that’s difficult to estimate without doing more research in this area; average age somewhere from around maybe 25 up to 50 – but you’ve got all different kinds of ages; and a really big diversity of different religious backgrounds. So, people coming from an atheist or agnostic background, a Christian background, a Jewish background, a Muslim background. Quite a few who come into Thelema from Buddhism, for example, or find ways of combining the two. So really, lots of different types of people. And professionally-speaking, many areas as well. Many people who are involved in the Arts in different ways, or in mental health, psychology – things like that. But also academics, IT professionals, teachers, educators. So, lots of different types of people.

SB: So you mentioned that there were perhaps a few more men in Thelema. Whereas groups that might be comparable, like Wicca and other forms of Paganism, tend to be much more strongly female. So do you have any opinions on why that might be?

MHW: Yes. That’s a good question. With groups such as Wicca what is important to remember is that, when Wicca emerged, the gender balance that we’re seeing today with a lot of women wasn’t really . . . that was different. Because when Wicca emerged, it came out of these ceremonial magical orders of the early 20th century, which were male-dominated to some extent. So what has happened in Wicca, in Neo-paganism, is this very strong integration with feminism, with second-wave feminism and radical feminism that we’re seeing in the 1970s. That intersection hasn’t been quite as strong, I think, within Thelema, although we definitely see the influence of it there as well. Thelema, and organisations such as the OTO, have stayed a little closer to this sort of ceremonial magical background that they’re coming out of, for different reasons. And there’s a lot of different reasons why that development hasn’t really happened in the same way there. But that’s a very fascinating disparity, I think, as well.

SB: So, in contemporary Thelema, to what extent do they base their practices on Crowley’s writings? And to what extent do they try and be a bit creative or reinterpret things? I mean, as he was obviously a very creative thinker, do they try and emulate that attitude as well?

MHW: Yes. Very much so. Both those things. Crowley is a huge source of authority for contemporary Thelemites, many of whom practise daily some of the rituals and spiritual practices that he advocated. For instance, Crowley advocated daily meditation, or the use of a magical journal – that is something that many, many Thelemites do on a kind-of daily basis. He also advocated the use of simple banishing rituals such as the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram, or the Star Ruby which is a sort of Thelemic banishing ritual that Crowley devised himself. And those are very popular as well. Also, a lot of Thelemites today participate in group rituals that Crowley wrote. One that is immensely important for a lot of people is the ritual called the Gnostic Mass – which Crowley wrote in 1913 – which is celebrated on a weekly basis somewhere across the globe within the contemporary OTO. And which has a lot of significance for many Thelemites today. But, of course, people are also immensely creative and also bring in practices, and symbols, and patterns of belief from other religious traditions as well. Like I mentioned, quite a few Thelemites are inspired by Buddhism, for example. And perhaps especially Tantric Buddhism and bringing in symbolism and practices for that, to different extents. Another thing that’s been developing in recent years is an interest in African Diaspora religions. So that’s particularly something that you can see in the US, with an increasing number of American occultists and American Thelemites bringing in practices and deities from things like Vodou, Santaría , Quimbanda, Palo Mayombe and things like that. So that’s a very interesting syncretism. So people are, of course, immensely creative as well. And that’s something that’s sort-of there in this religious system. Originally, Crowley was very sort-of firm on the idea that you should do what works for you. And you should be meticulous about documenting your magical practices and you should practice what works, instead of blindly following some sort of belief-centric system, essentially.

SB: And how about the gender politics in contemporary Thelema, as well? How much are they aiming to replicate the original? (15:00) To what extent are they changing, as well?

MHW: There has been quite an active debate that’s been ongoing at least since the mid-1990s with people, and especially women, I think, who have addressed things like perceived sexism and misogyny in Crowley’s writings. And also the gender disparity that we were talking about earlier: why aren’t there more women in Thelema? And what can we do to sort-of ameliorate that imbalance – to the extent that there is an imbalance? And one thing that’s of course new, is that today there’s a whole different language for talking about different varieties of gendered experience, and different forms of sexual orientations and practices as well, than there was during Crowley’s time. I mean Crowley himself was a very sort-of interesting figure, when it comes to gender. For instance, in some texts he suggests that he is sort of hermaphroditic, or androgynous, on a sort-of spiritual level. And in his diaries and his autobiography he writes about this as well. And he writes that he has combined the masculine and feminine virtues within himself, and that that is also reflected in his physique. So today we have labels such as gender fluidity, gender queerness, non-binarity and things like that, that weren’t really present in Crowley’s day. And that is something that’s very visible in this debate today, as well, and how that’s sort-of used. For instance in the OTO – the Ordo Templi Orientis – there is a system of referring to members as brother or sister. And there’s also been introduced a gender-neutral variety of that, so “sibling”: non-binary or gender queer members of the OTO can choose to be referred to as sibling, for instance. So that’s a very clear example of how that is actualised in the contemporary debate. Another example of that is with the Gnostic Mass, which in its original policy stipulates that the mass is performed by a priest and a priestess among other officers. And, originally, the policy for the United States Grand Lodge of the Ordo Templi Orientis states that the priestess should be a woman and the priest should be a man in Gnostic Mass celebrations that are open to the general public – which many of them are. Today, that policy has been . . . or this happened quite a few years ago, but that policy has been amended to say that the person performing the role of priestess should be someone who identifies as female and the person performing the role of priest would identify as male. So that, of course, includes that trans-gender women can perform the role of priestess and transgender men can perform the role of priests, regardless of where one is in the process of one’s transition. So that’s also a very good example of that, I think.

SB: And when it comes to people trying to maybe legitimate their arguments, or finding sources of authority for kind-of changing the – let’s say – traditional structures: what kind of narratives might they come up with?

MHW: Well, something that is really strong is sort-of appealing to Crowley’s own queerness, if you want to call it that. That is something that a lot of people who are arguing for revising these policies, and for bringing in what you could call the more sort-of inclusive way of looking at gender, they say: “Well, look at Crowley and look at who he was.” For his time, he was openly bisexual. He had a female alter-ego that he called Alice, who he sometimes took on the role of in rituals and in various social situations. So people point to that. There’s also quite a lot in original Thelemic doctrine that suggests that gender isn’t really . . . doesn’t really determine anyone’s value: that every man and every woman is a star. That’s a passage from the Book of the Law, and that’s something that a lot of people quote as well. However, there’s also quite a strong critique of Crowley in contemporary Thelemic debate. So a lot of people are also aware that some of the things that he wrote are problematic from a contemporary perspective. And they sort-of say: “Well, Crowley says this . . . but we don’t necessarily have to take everything Crowley says at face value. We can also acknowledge that he was a man of his time and that we’ve maybe come further in some of these issues today.”

SB: Ok. So how about the historical roles of women in Thelema? Could you tell me a little bit about that?

MHW: Sure. That is something that I’m actually starting my current research project that’s just starting now. It’s a three-year post-doctoral research project, funded by the Swedish Research Council that will be exploring that specific issue. I’m going to be looking at lives of three women in the 20th century Thelema, and their different roles in building this emerging religion. (20:00) So something that was really fundamental to many of the occult orders that emerged during the early 20th century is that women were able to take on leadership roles – in a way that they weren’t in the major religious institutions, during this time – and ascend to positions of really quite significant religious and spiritual authority. And that was also the case in the Golden Dawn, for instance, which Crowley was briefly a member of. And it was also the case in the early Thelemic movement. Several of Crowley’s female disciples and lovers held really important positions within the Thelemic movement. So one of them that springs to mind immediately, and is also one of the women that I’m going to be looking into in my post-doctoral research, is a woman named Leah Hirsig who was a Swiss American schoolteacher, and who co-founded with Crowley the Abbey of Thelema at Cefalù, on Sicily, in 1920. And she was basically his right hand for a few years, there. He dictated important texts to her, and she wrote – in all likelihood – commented and edited and contributed to that as well. And she was also really instrumental in sort-of steering the Thelemic community which was scattered across the globe around this time. She was also Crowley’s Scarlet Woman, which is a title that he assigned to some of his most important female disciples and lovers. So, to that extent, she was seen as the sort of semi-deified counterpart of him as the Beast, 666. And she also, at the Abbey of Thelema, took on a very, very important ritual role as the Scarlet Woman. She eventually claimed herself to be the goddess Babalon incarnate. And she also presided over Crowley’s initiation to the highest degree in his magical system which is called the Ipsissimus degree. So she played a really important role in that. Another woman who was very important, whose life I will also be looking into, is named Jane Wolfe – who was an American silent film actress, who was also with Crowley at the Abbey of Thelema, and studied under his tutelage, and then went back to America and was really fundamental in establishing the Thelemic milieu in the US. And something which is often overlooked about these women is how really important they were, and how fundamental they were. For instance, right now there’s this TV series that’s being . . . I can’t remember what station it is, or what channel, but on the life of Jack Parsons, who was one of Crowley’s more colourful, American disciples in the US. And Parsons gets a lot of publicity for various reasons. He led a very interesting life. But someone like Jane Wolfe, who was very sort-of organisationally important – and over a much longer period than someone like Parsons, for instance – gets a lot less press, and a lot less sort-of attention, because she plays a quieter role. But she was really formative. And that’s, a lot of the time, what happens with women in religious communities. They don’t get the spotlight. But they’re there managing everything and making sure that the day-to-day operation actually works. So that is something that is, sadly, quite often overlooked.

SB: Do you think that attitudes towards women in Thelema have generally reflected wider society’s attitudes?

MHW: Yes. Definitely – to an extent, of course. In society at large, of course, there are issues with women as leaders in a lot of different fields, where women aren’t really allowed, or not accepted, as leaders to the same extent as men. Or women who take on leadership roles are also often perceived in a more negative light than men. And I think those issues are reflected in the Thelemic community as well, to some extent. Or at least they have been, definitely, historically. And also this sort-of expectation that women are supposed to take on more emotional labour, and more sort-of chores – like preparing, and cooking, and cleaning, and doing those types of things – while the men get to sit around and have interesting conversations. I mean, that’s a little bit of a stereotype, but sometimes you see that happening definitely in occult history, as well.

SB: OK. So, changing tack slightly: when it comes to occultism and esotericism, they are famously kind-of secretive. So how did that effect your research and the methods that you used to research this?

MHW: Yes. That’s a good question. And it is, of course, a challenge to study these movements. Some of the rituals, for instance, that are performed by the OTO today – such as the initiation rituals – those are secret, and they’re not open to initiates. I handled that by not writing about those parts of the tradition, whatsoever. Some researchers within this field have dealt with that by conducting sort-of open participation observation: seeking initiation in occult orders, and then describing the rituals. And I chose not to do that because I felt it would be ethically quite troublesome. And also it wasn’t really the aspect of the traditions that I was interested in for the particular research that I did for my PhD, anyway (25:00). But it is something that you definitely come across, to a certain extent. And there’s always a lot of sensitivity that’s required as a researcher, I think, in sort-of determining what you’re actually being invited into as a scholar, and what you’re being invited into as a friend – or someone who’s perceived as a kindred spirit. And that’s something I’ve had to deal with a lot, with conversations of a more delicate nature, during my fieldwork. And when I’ve published from my research, there are things that are being left out for that reason. But that’s the case with anyone who does any type of ethnographic research, I think.

SB: Well, Manon – thank you so much for joining us. I hope you enjoy the rest of your conference.

MHW: Thank you so much.

SB: And thank you for joining the RSP.

MHW: You’re welcome.

Citation Info: Hedenborg White, Manon and Sammy Bishop. 2018. “Negotiating Gender in Contemporary Occultism”, The Religious Studies Project (Podcast Transcript). 10 December 2018. Transcribed by Helen Bradstock. Version 1.1, 2 December 2018. Available at: http://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/negotiating-gender-in-contemporary-occultism/

If you spot any errors in this transcription, please let us know at editors@religiousstudiesproject.com. If you would be willing to help with transcribing the Religious Studies Project archive, or know of any sources of funding for the broader transcription project, please get in touch. Thanks for reading.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The views expressed in podcasts are the views of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of THE RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROJECT or the British Association for the Study of Religions.