Budding theorists may find themselves conscripted into the ideological battles over the nature of religion or, to put a finer point on the argument, how scholarship in religious studies should be done. For even if one has not openly sided with a particular group regarding what ‘religion’ is, it is very likely you do have some inkling regarding how scholarship in religious studies should be done. As Russell McCutcheon notes in this interview one of his teaching texts is a brief opinion from a lawsuit in 1893 (Nix v. Hedden) regarding the nature of tomatoes. Are tomatoes fruits or are they vegetables? And why does it matter?

For the Purposes of…

McCutcheon, like the presiding judge in this case, is not terribly interested in the intrinsic nature or essence of the ‘tomato’ but rather what the tomato will be for purposes of trade and tariffs. This case upheld the Tariff Act of 1883 which did not charge a tax on imported fruit but did charge a tax for imported vegetables. If this case appears to have nothing to do with the battles over ‘religion’ look again and ask what happens when you supplement the word ‘tomato’ with ‘religion.’ Make the categorical division not between ‘fruit’ or ‘vegetable’ but rather envision a litany of possible interpretations such as ‘religion’ is at heart really about wielding knowledge and power, money and manipulation, primordial man’s explanation of the terrors and wonders of the natural world, individual neurosis, or a deep, personal and private encounter with an omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent deity, etc. How quickly seemingly solid categories come unraveled… suddenly, I am much more comfortable becoming an arbitrator on anything, tomatoes included, than on what I supposedly study.

Okay, let’s return to the tomato argument for a moment as perhaps it will shed some light on our predicament. In order to come to a conclusion we must look at precedent (i.e. how has the word been used before). We can also compare dictionary entries and call ‘expert’ witnesses. Oxford Dictionaries even weighs in on the argument… it seems that this issue arose because scientists and cooks use the word differently. According to Oxford Dictionaries, scientifically speaking, a tomato is a fruit. In the culinary world, the tomato is referenced as a vegetable because it is savory. Notice that the argument has morphed from pertaining to what category the tomato is in based on its qualities to a matter of who is doing the speaking.

One need only remember that Gershwin classic “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” to know that how one pronounces a word denotes not just dialectic difference but class distinction as well.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zZ3fjQa5Hls]

The tomato has a long and varied history. A native to South America, the term originates from the Nahuatl tomatl. Although recently heralded as a cancer-fighting food, historically the tomato has an infamous reputation.

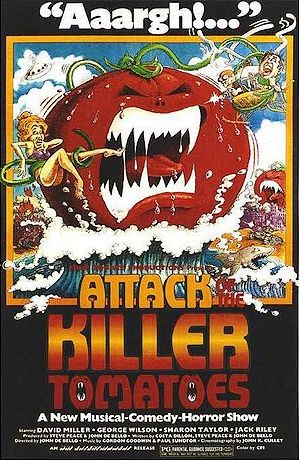

A member of the night shade family, the tomato has sporadically been labeled as poisonous, or at least suspect, and some naysayers have even gone so far as to dedicate websites to (www.tomatoesareevil.com) or make cult classic films about their true diabolical nature like Attack of the Killer Tomatoes. And many readers are probably aware of the tales of throwing rotten tomatoes at bad actors! What may come as a surprise to these same readers is that tourists in Spain can pay $13 to participate in the world’s largest tomato fight!

Who knew that the tomato could be so polarizing?! Who knew this tiny fruit/vegetable could arouse such vitriol?! Fruit? Vegetable? Poisonous? Nutritious? Good? Evil? Is it a panacea or pandemic? It seems that the tomato defies our categories. It appears to transcend barriers. It is irreducible. And yet where are the departments of Tomato Studies? Where are the calls for the study of sui generis Tomato?

So before we sharpen the pitchforks and enter the fray, we should note that this doesn’t seem to be an either/ or (as in a tomato must be either a fruit or a vegetable) battle at all but a squabble addressed best by thinking about context. Is the tomato a fruit or a vegetable? Is it good or evil? My answer to the ‘tomato’ question is one I offer frequently regarding the ‘religion’ question, much to the chagrin of my students, when they ask questions like “are Mormons Christians?”… it depends on who you ask and it depends on the context. And in a classic McCutcheon twist, I might ask them, who gains and who loses if we admit or deny Mormons (or tomatoes) entry into the halls of Christendom (or fruitdom)? And are any Mormons (or grocers or botanists) stopping by our classroom to ask our opinion?

Essence of Tomato

So we may never know the true, deep meaning, of ‘religion’ or ‘tomato.’ ‘Tomato’ as a Platonic ideal may always elude us. ‘Tomato’ like ‘religion’ may defy our categories. By using this example, McCutcheon is pointing out to us that perhaps we are too wedded to our conceptions of sui generis (unique, irreducible, pristine) ‘religion’ to see the social and political implications on our scholarship. Suddenly, the situation is a lot less dire when I apply these same questions to the enigma of the tomato. But before we dismiss the tomato controversy, we need to remember that the above case was judged by the Supreme Court. So, what do we do if declaring the true essence of ‘tomato’ or ‘religion’ is not within our jurisdiction as academics?

The judge in this case, along with McCutcheon, appears to nudge us towards a more terrestrial interpretation. Perhaps we will never know what a tomato, vegetable, or a fruit really is (ontologically speaking) but for purposes of trade and tariff, we can decide what a tomato will be. After all, our categories themselves (fruit and vegetable) as well as the term ‘tomato’ are products of language. Our categories and words could have been otherwise and in other cultures often are. As McCutcheon might argue our categories and words are contingent, conditional, and contextual.