Here Be Monsters

Seven or so minutes into David Robertson’s interview with Rice University’s Jeffrey Kripal, Kripal cuts to the heart of an issue that plagues contemporary religious studies scholars: Do we have the tools and will to seriously examine experiences of the fantastic in the present age?

In my response today, I hope to achieve two things. First, I want to discuss Kripal’s presentation of the field’s latent crisis of emic/etic perspective regarding religious experiences. His explorations of the fantastic should be exciting to many listeners. Go right ahead and take a look at Mutants and Mystics (2011) or Authors of the Impossible (2010). They are worth your time, and I believe it is possible that in the interview he undersold the significance of attempts toward understanding the resurgence of supernaturalism in our present era.

Second, I think it is necessary to challenge the way Kripal avoided the field’s problem with sui generis approaches to religious and paranormal experiences. Elevating consciousness as a replacement for older comparative, phenomenological categories such as the holy, sacred, or numinous does not escape the established critiques from folks like Russell McCutcheon or Tim Fitzgerald. It only defers judgment until some future moment when science can better explain consciousness or paranormal experiences in material ways. Or, worse still, it takes the gambit that scholars can never truly understand our world through observation. Many beginners in religious studies are advised to consider naturalism as the cornerstone of our field. If we supplant it by admitting that consciousness is sui generis and unknowable, as Kripal appears inclined to do, then are we not trying yet again to move religious studies out of the humanities or human sciences and back into the realm of theology? (Or simply rehashing the arguments over comparativism between Paden and Wiebe from the late 1990s?) Though our field may not fully embrace the scientific method as its methodology of choice, its premises of knowledge acquired through empirical observation and verification remain the philosophical bulwark for our work.

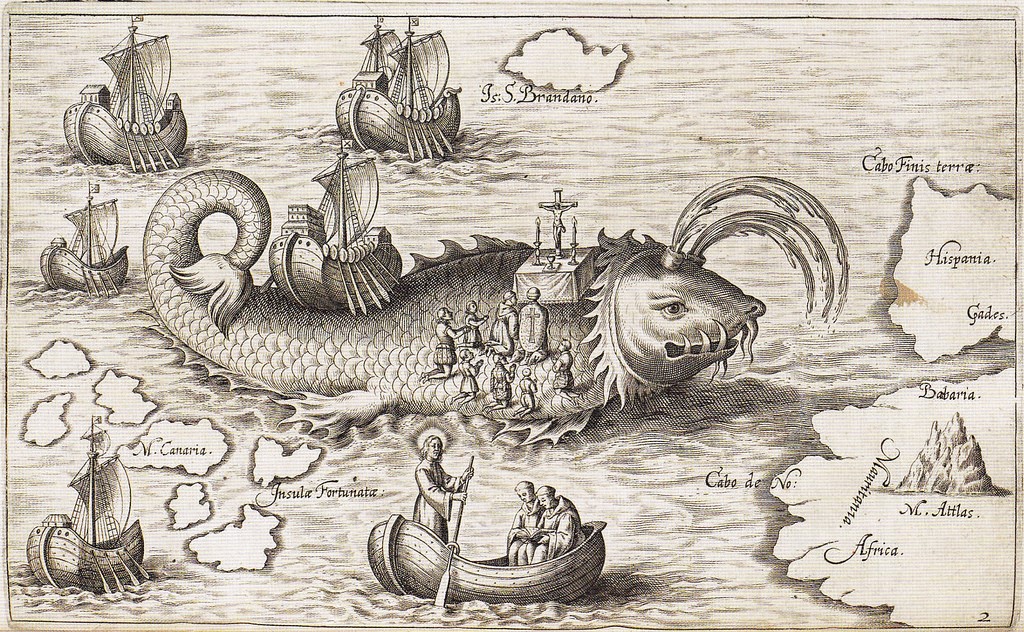

In sum, Kripal’s approach identifies new territory for scholarly exploration of paranormal experiences, but it also limits those explorations by failing to heed the lessons learned in previous expeditions. Ironically, the monsters were marked on the map; we should have believed the stories.

The Lasso of Truth

Supernatural. Paranormal. Fantastic. What are the boundaries for discussing these phenomenon? Do we take a skeptic’s approach and deconstruct an informant’s experience with the lenses of scientific reductionism? Shall we build a social world that frames phenomenal experiences to explain them away as historical products of pre-scientific thinking and superstition? Are we bound to believe the stories in full or analyze them as if they were so?

I see one version of our field’s history as haunted by these questions. It is a procession of ghosts fighting over the issue of the experience of the religious–the sacred legacy stretching from James and Durkheim through Otto to Eliade and J. Z. Smith. Modernity’s crisis of truth, the onset of relativism and deconstructionism, has meant that religious studies has been continually frustrated over the issue of authenticity in its sources and subjects. How can we know that ancient religious agents really believed the bear would lie down and offer itself to the hunters as a sacrifice (my favorite example from J. Z. Smith’s Imagining Religion)? Perhaps this is the thorn in our side from our Protestant legacy. We are left to forever doubt our own interpretative models and be stuck between the absolutism of the insider’s emotion and the skepticism of the outsider’s inability to be or think like the insider.

Kripal’s presentation of the key issue in the study of the fantastic goes like this: If something fantastic happened in the past, then we are better able to feel sympathy for that experience because it is historical. If we cast it aside or call it superstition, then we do so without harming a living informant. It is a difficult part of our work when we must listen to an informant tell an extraordinary tale and then reserve judgment on whether we think the story is true. It is not just that telling someone face-to-face that you do not believe their story is difficult. In practice, this breaks the boundaries for gathering observations. We can then be won or lost as listeners who also believe or understand. Historians are blessed with a distance that fosters objectivity rooted in naturalism and skepticism. Within the field, supernatural explanations do indeed seem to fall beyond the pale as truths. The “ontological shock” of the past is not accessible in the present.

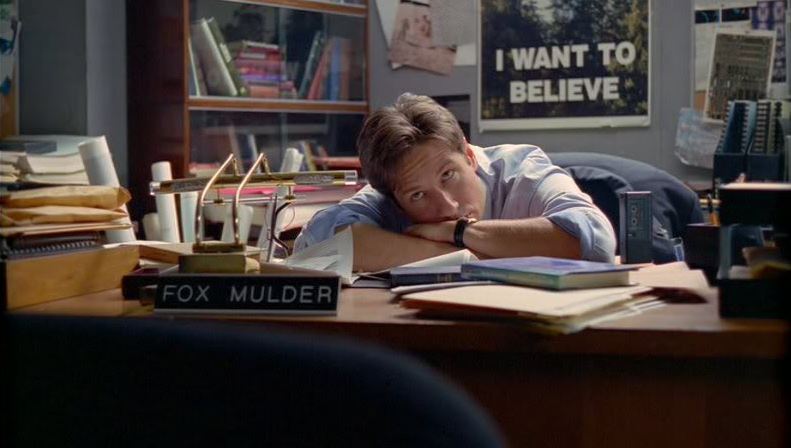

When studying living agents, however, Kripal argues that our field has been largely “unwilling to take the fantastic seriously in the present.” This lack of seriousness can be a micro-aggression of disbelief or scoffing at an exaggerated tale. Or it can be the scientific dismissal of an experience by explanations rejected by the observer themselves. But it was real to me, they might say. Are we to reply “I do not believe you”? The question of the authenticity and reality of these experiences are the heart of the issue for those who experience the supernatural or paranormal. Thus, Kripal says he does not “understand how as scholars we can just bracket [the question of ontological truth]. I understand why we can’t answer that question, but I don’t agree that we should just push that question off to the side.”

Indeed, for most of the last century ethnography demanded that observers bracket their own worldviews. Were you pursuing your interpretations (the etic) or the interpretations of your subjects (the emic)? Even modern concessions to the role of observers in influencing the things they document, as in the work of Karen McCarthy Brown, do so in ways that highlight the distance between the ethnographer’s world and the world of her subjects.

Kripal says that to deal with the paranormal, observers cannot be phenomenologists secluded from the truth claims of their subjects. Truth–that of the informant and the observer–is collapsed into a shared faculty of experience called consciousness. “These most extreme and fantastic religious experiences,” he says, “might well be our best clues as to what the nature of consciousness really is, below or above our social egos and these sort of superficial forms of awareness that you or I are in at the moment.” Kripal need not believe the particular details of alien abduction or out-of-body teleportation because the mode of experiencing these events is real–it is our consciousness and that makes it “the ground of all religious experience.” It is “the new sacred.”

There are plenty of ways to discuss this remarkable exchange, but Kripal falls back on the narrative that led our field to criticize Eliade or Otto’s claims that the sacred was sui generis. Consciousness, he says, is sui generis.

Part of the effect of this radical move is that Kripal is binding his informants with, to borrow a popular culture reference, a lasso of truth. He compels them, wills them to be truthful because the ground of the experience cannot lie to them. After all, it was their experience. If I am following correctly, our informants merit our trust not on the details of their experience, but rather on the mode of experiencing. Those experiences then fall either on the side of the ego and the everyday or the side of the extraordinary where consciousness is universal, groundless or “empty.”

Shall we put aside the issue that we have not explained how to differentiate between types of experiences apart from the informant or the observer’s explanations? Or how groundless experiences in our consciousness are anything other than wordplay for the sacred? How have we improved our lot by this shift to the term consciousness? Have we not just substituted ego and emptiness for homo faber and homo religiosus?

Like Kripal, I think it is unlikely that most (or perhaps any) informants are describing an experience from our world when they narrate an alien abduction. So I fail to see how we can do significantly more than say they have told him a story they believe is true. As observers receiving such a story, I find it our duty to walk the line that holds us from letting the veracity of a claim dictate our field’s observational models or orientations. A single informant’s truth is anecdote, not evidence. Nor does a body of similar anecdotes become truth through the weight of repetition. If corroborating evidence fails to appear, it does not rob an anecdote of meaning or significance. For we do not set our business upon the truth-claim, but rather on the value of the story. Though Kripal acknowledges his informants’ desire to place ontologies at the center of their experiences, this should not compel us to then reassert the grounds of our field’s ontologies. Should we not feel uneasy when told that it is appropriate to do so? Have we really escaped the trouble of sui generis critiques by replacing the sacred with an something that Kripal says cannot be measured or known “in principle because it is not an object”? Though we need not be utter materialists or empiricists to do our work, are we not placing our interpretations at risk when we place them on immeasurable and unknowable foundations?

Truthiness

Let me try another tack to conclude my thoughts on the issue of truth and its relationship to scholarly discussions of the paranormal and supernatural. In the pilot episode of his television show The Colbert Report in 2005, Stephen Colbert introduced western audiences to truthiness. “We’re divided between those that think with their heads and those that know with their hearts,” Colbert said. “The truthiness is that anyone can read the news to you. I promise to feel the news at you.” Truthiness is the simulacrum of the truth we wish existed “in our gut.” Or, as he said in an interview for The Onion, “Facts matter not at all. Perception is everything.”

So how should we then perceive experiences of the paranormal? Is it the truth of the sacred in the gut of religious studies? Or is it a semblance of truth that feels better than the materialistic, reductionist alternative? Are these our only options?

In Authors of the Impossible, Kripal attempted to show how both religious and scientific registers came to be seen as failing to explain paranormal experiences for a wide range of pseudo-religious personalities. For folks like Charles Fort, for instance, science had all the answers. Later, science became a target of great skepticism, a “trickster” that appeared to offer answers but could not actually explain much that mattered. In Kripal’s hands, this argument takes a new shape: if science cannot address consciousness and it is universal, then perhaps it is that substance or ground upon which the sacred can also be found. It seems to have a sense of truth to it. It feels like it could make the fantastic possible. But how are we to be sure?

Pivoting in the last few minutes, Kripal argues that the thing that we need to truly understand paranormal experiences is symbolic imagination. In our efforts to embrace difference and “demonize” sameness, we seem to have lost the ability to appreciate radical experiences. We are too interested in reducing the world to scientific claims and are insulated from the opportunities of experiences that break the mold. This is the mystical invitation–the root of much inspiration for authors of science fiction and comic books in Mutants and Mystics–that reveals the paradigm shift Kripal asks for: to have the field deal with the paranormal. Can we treat the fantastic seriously on these terms? Let us know how you feel in the comments.