Reading the interview with Paul-Francois Tremlett makes me think about why certain philosophical figures of thought such as assemblage and rhizomes, but also the vitalism of New Materialism, are currently experiencing an increasing boom in the humanities and natural sciences. Do such thought-pictures add epistemic value to the analysis of religious change?

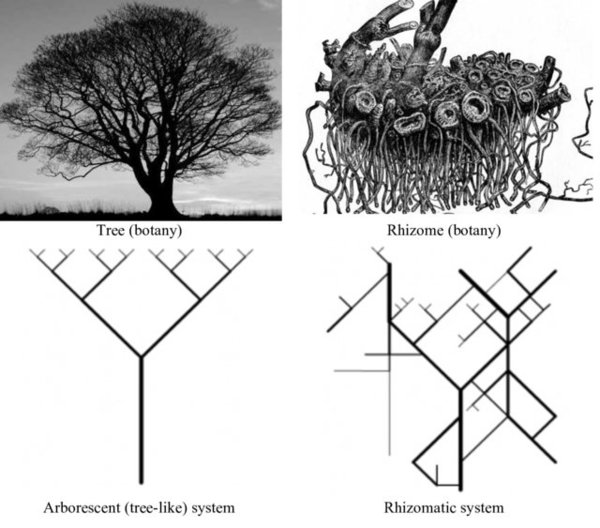

Deleuze and Guattari, prophets of New Materialism and Posthumanism, tell us that notions of a human ‘self’ and ‘nature’ are misleading. They propagate heterogeneity, multiplicity, nomadic science, the ‘organless body’ (corps sans organs), and they create new figures of thought such as assemblage and rhizome. By assemblage, both philosophers understand unformed matter, destratified forces and functions through which spaces emerge and through which territories can be deciphered. Rhizomes spread wildly sprawling horizontally and egalitarian in space. Assemblage and rhizome presuppose flat ontologies in a double sense of the word.

Fig. 1: An comparison of arborescent (simple, linear, hierarchical) and rhizomatic (complex, multiple, non-hierarchical) systems (from Gough 2011: 2)

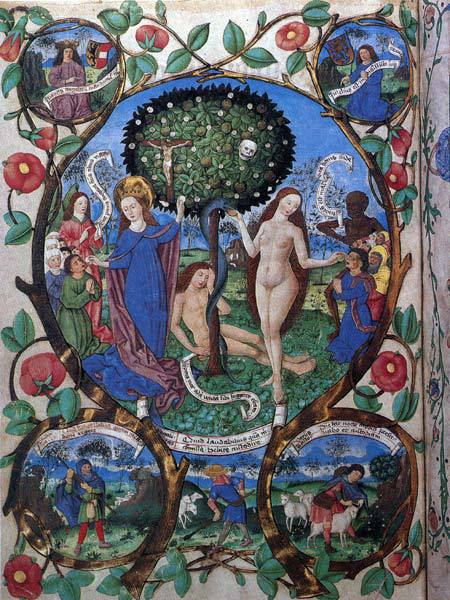

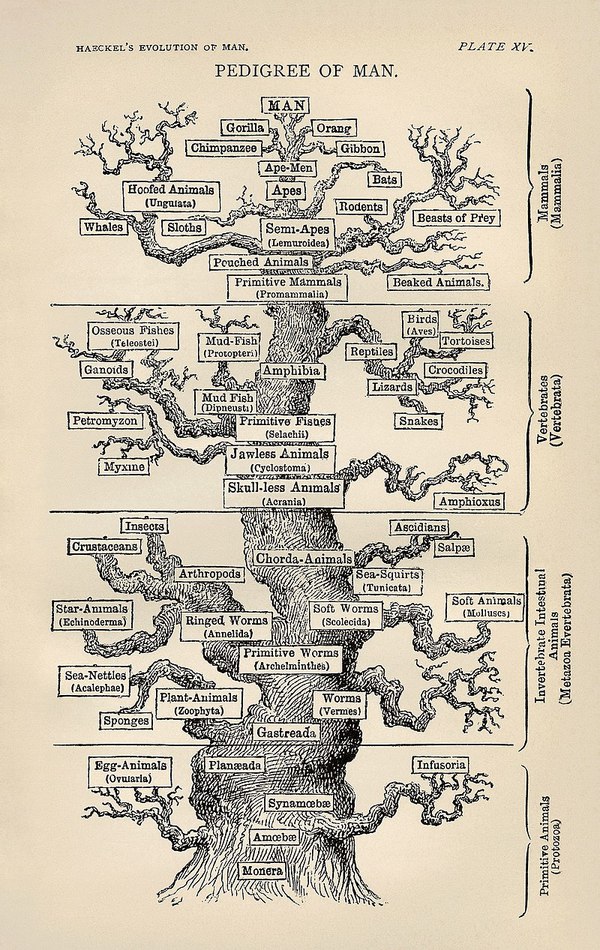

The Haeckelian tree, against which Deleuze and Guattari argue, describes developments upwards, which seems attractive to the hierarchical thinking of evolutionism and its teleological categories. The “tree of life”, as Ernst Haeckel popularized it in the 19th century for evolutionary biology, is the transfer of a Christian theological image known since the 5th century.

Fig. 2: Berthold Furtmeyr, Tree of Death and Tree of Life, Salzburg Missal (15th c.)

Fig. 3: Tree of Life by Ernst Haeckel, from The Evolution of Man (1879)

Paul-Francois Tremlett wants to test the alternative images of Posthumanism in the field of religious studies. The Filipino Christian charismatic movement El Shaddai is an illustrative example of this, mentioned in the interview. Inspired by the category of rhizome, as I understand him, Tremlett develops the concept of ‘generative interactivitiy’, which shows how different urban spaces transform and turn into new spaces. It is not the shaping individual, such as the El Shaddai leader, that interests him, but “material forces through which El Shaddai is embedded in a series of other transformations.” Tremlett sees religious change as an essentially rhizomatic process that can also be described as an assemblage: “As an assemblage of forces and elements that are always moving, and it’s through that process of emotion, that new assemblages come into being.” Tremlett understands a religious movement like El Shaddai as a ‘material religion’ and analyzes change through the media foundations of that religion. Religious change, as I understand Tremlett, is conceived essentially as movement in space. Analytical suggestions of the material turn and the spatial turn are combined. This idea is comprehensible and plausible to me, especially since the message of El Shaddai appeals above all to Filipino overseas workers, i.e. migrants.

At the same time, however, the image of the rhizome creates the impression of a rather arbitrary and irregular dynamic of religious change. The model of the rhizome is reminiscent of a map of subway connections, a snapshot in time, and does not exhibit any historical depth. The rhizomatic in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari has something anarchic, elusive. More generally, the question arises: who and what are the real actors in such posthumanist narratives: microbes, viruses, air and ocean currents, financial flows, algorithms, control modules, artificial intelligences, transport infrastructures, electricity networks, the Internet …?

It is certainly fascinating to describe religion through a system of information channels. But isn’t religion something man-made? Without body, senses, emotion and communication, there is no religion. I miss the human individual in the analytical translation of rhizomes. Religious-aesthetic concepts seem more appropriate here. I am thinking, for example, of Birgit Meyer’s analytical concept of ‘aesthetic formation’, which is quite helpful for the study of change, since it refers both to a ‘social entity’ and to the ‘process of forming’: “‘Aesthetic formation’ captures very well the formative impact of a shared aesthetics though which subjects are shaped by tuning their senses, inducing experiences, molding their bodies, and making sense, and which materializes in things” (Meyer 2009: 7).

From the perspective of the history of religion, I miss the dimension of ‘time’ in the proposed analysis of change. Assemblage and rhizomes are largely spatial analytical concepts. Deleuze and Guattari unfold a “geography of reason,” “a geophilosophy describing relations between particular spatial configurations and locations and the philosophical formations that arise in them” (Gough 2011: 7). Describing religious change as rhizomatic movement in space and religions as assemblages certainly reveals interesting patterns. Other patterns, essential patterns as I think, remain invisible.

Narratologically, science is a “narrative praxis” through which reality is not only described but also produced (see Herman 1998). The image of the rhizome comes from biology and biology, according to Donna Haraway, can be understood as “the fiction appropriate to objects called organisms; biology fashions the facts ‘discovered’ from organic beings (Haraway 1989: 4, after Gough 2011: 4).

Posthumanist narratives that decenter the human, rehearse a non-anthropocentric way of looking at things, animate dead matter, and propagate new ontologies beyond Descartian subject-object divisions currently appear attractive. These narratives are, in my view, symptoms of crisis. The grand dystopian narrative “Anthropocene” proclaims that catastrophe is near and action must be taken. Posthumanism, however, deconstructs the agentic subject. The processual alone is real. “[T]here is no such thing as either man or nature now, only a process that produces the one within the other. [….] The self and non-self, outside and inside, no longer have any meaning whatsoever”, as Deleuze and Guattari state (1983: 2).

This narrative of complexity and diversity of reality often causes irritation, confusion and often fear. One reaction to this are the narratives of the great simplifiers like Trump, Bolsonaro or Modi. They very successfully reduce the complexity of the world to dual black and white opposites and praise the strong individual. This is in stark contrast to narratives of New Materialism, which seek to push the human individual down from its complacent throne. The milieu of an intellectual minority, in which processual complexity and vitality of matter is celebrated, is thus juxtaposed with a (still) jubilant mass, who are promised salvation of the self and the world by simple means. Powerlessness and self-empowerment are antagonistically opposed to each other. In short, I understand the fascination with the philosophical narratives of New Materialism and Posthumanism as intellectual coping strategies for one’s own powerlessness. Such narratives are moral stories, for they point to the anthropocentric hubris of (Western) man, which must give way to humility before Gaia, Mother Earth. Otherwise, doom looms. In my view, this is the larger picture of the zeitgeist that makes Posthumanism attractive. However, the philosophical concepts developed there are difficult to translate into empirical research.

The narratives of New Materialism certainly reveal fascinating cross-connections, albeit with rather blurred outlines. Empirical research in this field is scarce and so one can wait with curiosity for further empirical tests of the philosophical instruments of Posthumanism.

References

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Herman, David (1998). “Narrative, Science, and Narrative Science.” Inquiry 8 (2), 379-390.

Gough, Noel (2011). “Performing imaginative inquiry: narrative experiments and rhizosemiotic play.” Global Education 40 (4), 3-13.

Haraway, Donna J. (1989). Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge

Meyer, Birgit (2009). “From Imagined Communities to Aesthetic Formations. Religious mediations, sensational forms, and styles of binding.” In: Aesthetic Formations. Media, Religion, and the Senses, edited by Birgit Meyer. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, 1-30.