A response to “Holocaust Museums as Sacred-Secular Space”

Dr. Alba convincingly discusses the ways that Holocaust museums have become sacred spaces through their promotion of “ritualized behaviors.” Holocaust museums, she argues, have two roles in this regard: the negotiation of the “tension between… Jewish memorialization and broader memorialization” and within Jewish memorialization on its own terms. The latter is the focus of her interest because of the unique role that museums play in a religious landscape still unsettled by the Holocaust. She observes that in “Jewish theology, in the Jewish world… there is absolutely no agreement” on the meaning of the Holocaust, on how to commemorate it, and on how to incorporate it into communal life and practice. As a result, “there’s almost no other forum […] where one can […] actively play out what it means to commemorate the Holocaust in the way that one can in a Holocaust memorial museum.” Synagogues and cemeteries, Dr. Alba argues, have long-standing rituals that do not account for what she identifies as a theological rupture caused by the Holocaust. Incorporating this theological rupture into commemorative practices is something that “happens more in a space like a Holocaust Memorial Museum.” Further, museums are meaningful and helpful because “for the majority of those who lost people in the Holocaust, there are no graves, there are no places to go. But you need a place to go. There has to be somewhere where you can go and you can do that mourning.” That place is a museum.

I would like to suggest that there is another such space – a space that can function as an ersatz gravesite; a space that can engender new rituals and liturgies of commemoration; a space that can join both public and private, Jewish and non-Jewish, memorial practices. But it is a space only metaphorically: books. My current research project explores books that, in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust (and also beyond), have played roles that more recently have come to be associated primarily with monuments and memorials, especially memorial museums. Of course, there are many obvious differences between the types of commemorative work that can be performed in a public, built space, and those that happen in the context of individual reading, or even group reading. But there are also commonalities. I would like to examine two of Dr. Alba’s examples of the features of Holocaust commemoration in museums to show how they have also applied in literary contexts.

The first is Dr. Alba’s observation from her fieldwork that many survivors come to Holocaust museums because, “here I feel close to those I lost.” With no graves to visit, they come to museums. The focus of my research is a Yiddish-language book series published in Buenos Aires from 1946-1966, edited by an Argentinean Jew originally from Poland named Mark Turkow.[1] The book series was titled “Polish Jewry” (dos poylishe yidntum), and ultimately ran to 175 volumes. Polish-born, Yiddish-speaking Jews, constituted the majority of the approximately 300,000 Jews in Argentina in the mid-1940s, so there was a relatively large homegrown audience for Turkow’s book series. But it comprised works by authors from around the world and was distributed globally—wherever there were Yiddish readers to be found. In the fourth volumes of the series, My destroyed town Sokolov: Descriptions, images, and portraits of a city of murdered Jews (1946), the author, Perets Granatshteyn (also spelled Peretz Granatstein), writes in the introduction: “Sokolov is destroyed. Not a single Jew is there. The cemetery was destroyed and the ground plowed under…[2] No memory of our past remains there. Therefore this book is a matseyve (gravestone).”[3] He goes on to recommend that all survivors from Sokolov “should, from time to time, ‘visit’ the graves of their ancestors by reading this book and sadly remembering.”[4] The term matseyve is the Yiddish word for gravestone, not for monument or memorial; in other words, he associates his book with a physical object, in order also to claim the preexisting ritual and liturgical traditions associated with cemetery memorial practices. This kind of vision for the book series as a whole and the individual books in it are found throughout the series and not only limited to books, like Granatshteyn’s, that have specifically commemorative aims. The series also includes works of fiction, poetry, social and cultural history, and family memoirs; even these are integrated into a framework that sees books as being able to create, in the term of the series editor Turkow, a bikher-monument, a monument of books.

How it is that books can do things more commonly done by museums, monuments, and memorials? There are, of course, many explanations, drawing on the long-intertwined history of literature, monuments, and museums. One particular explanatory model that resonates strongly with the issues raised by Dr. Alba emerges from a particular story that she tells about an archetypal Jewish book—a Torah scroll. Dr. Alba describes her decision, while a curator at the Sydney Jewish Museum, to put on display a Torah scroll that was damaged during the Holocaust. The curatorial team ultimately put it in the timeline of Jewish history as the symbolic representation of the “rupture of the Holocaust.” To make the point in the exhibit, she cited the writer Mark Baker who himself cites a Talmudic legend about Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion, who was wrapped in a Torah scroll and burned at the stake during the Hadrianic persecutions of the second century CE. The rabbi famously told his students that although the parchments were burning, the letters were flying away (Talmud Bavli, Avodah Zarah 18a). Dr. Alba presents Baker as implying that a belief in the eternal nature of Holy Scripture and by extension of a special covenant between the Jewish people and God, is no longer possible. For Dr. Alba, the damaged Torah scroll in the museum is an emblem of failed theodicy; for the “majority of Jews… these classical theodicies are unpalatable.”

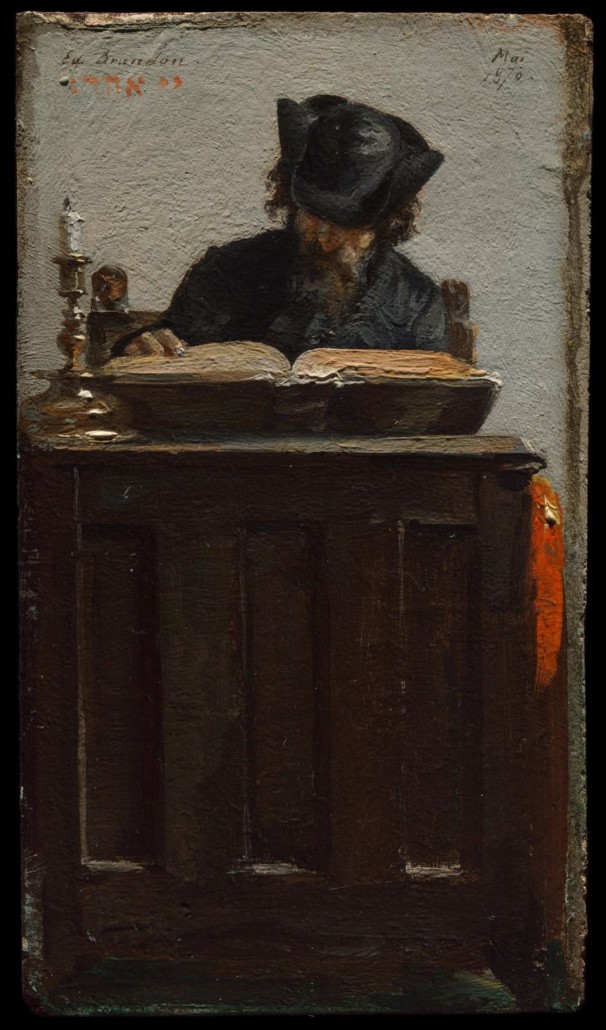

Above, detail from the Knesset Menorah, a gift of the British government to Israel, showing the death of Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion. He is on his knees, his head bent forward. Flames rise on either side of him in the sculpture. Image from By Tamar HaYardeni – Own work by the original uploader, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62597275.

But perhaps rather than a theodicy, this story is an example of cultural innovation necessitated by catastrophe and catalyzed by a reworking of the relationship between people and texts. The story of Rabbin Haninah ben Teradion itself echoes the story of the first century Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, who, knowing that Jerusalem and the Temple would soon be destroyed, asked Vespasian to spare the town of Yavneh and its sages. Judaism’s transformation from a cult- and site-based religion into a geographically unconstrained, text-centered religion is reflected in this story. It represents a metaphoric and a social shift from institution to text. The story of Rabbi Haninah then emphasizes the flexibility of texts: as long as another copy of a book exists, or as long as its contents are remembered, a book – unlike a building, unlike a place – cannot truly be destroyed. Dr. Alba describes how museums have, within a secular framework, come to shape religious understandings and to promote ritual commemorations of the Holocaust. An author like Perets Granatshteyn shows us another place that does much the same thing: books.

[1] For a brief overview, Jan Schwarz. (Winter 2016), “A Portable Library for Polish Jews,” PaknTreger.

[2] Perets Granatshteyn, Mayn khorev shtetl sokolov: shilderungen, bilder, un portretn fun a shtot umgekumene yidn, Dos poylishe yidntum 4 (Buenos Aires: Tsentral-farband fun Poylishe Yidn in Argenṭina, 1946), 4.

[3] Granatshteyn, 8.

[4] Granatshteyn, 8.