An Important Intervention

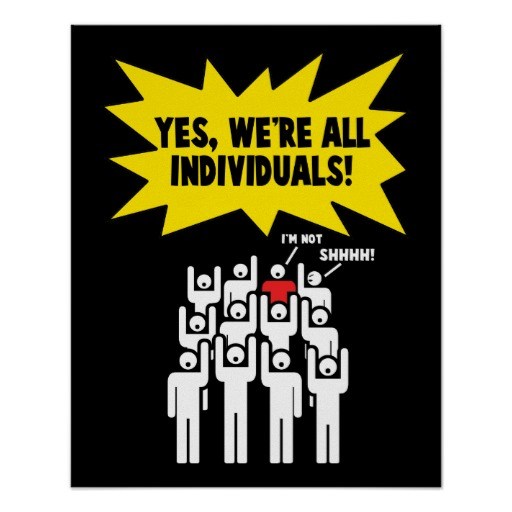

Veronique Altglas is to be commended for her intervention into the contemporary academic discussions and (often uncritical) usage of the concept of bricolage. As she rightly suggests, the naïve view that the acts of cultural improvisation of a modern bricoleur are unconstrained and unlimited by anything beyond the free and willful activity of his or her own individual whims is long overdue for retirement. And, in the wake of her efforts, one certainly hopes that the analytic appeal to such a naïve sense of radical cognitive autonomy becomes increasingly difficult to maintain.

However, I must admit that I do wonder to what degree such an extreme view ever actually had a significant conceptual hold over sociological analysis in the first place. Throughout her interview, Altglas is very careful to emphasize that, of course, bricoleurs cannot be so extravagantly free in their acts of picking and mixing among cultural representations because, after all, not all cultural resources are available to them. This is both an important intervention and, simultaneously, a rather obvious and nearly tautological point: people cannot pick from, or mix with, resources that are not available to them. One wonders if there were ever actually any scholars who would have argued otherwise, or who have genuinely suggested that cultural context plays no role whatsoever in the syncretic activities of modern bricoleurs.

Even Thomas Luckmann, who Altglas uses as her go-to example of a sociologist who supposedly endorses this radically individualistic stance, doesn’t really express such an extreme view as the one that Altglas uses as her foil. She quotes Luckmann as having said that, in the case of contemporary bricoleurs, “anything goes,” and suggests this view as indicative of a position that holds the creative powers of the bricoleur to be “unlimited.” However, in the very sentence that Altglas is quoting, Luckmann, himself, characterizes his claim as little more than a suggestive “exaggeration” (Luckmann 1979, 136; cited in Altglas 2014, 2). In fact, what Luckmann had in mind here seems to be precisely the same point that Altglas herself eventually comes around to in the final portion of her RSP interview: When religious organizations begin to lose their hold as authoritative interpreters of available cultural representations, especially in a context of easy access to a large and highly diverse spectrum of informational resources, this can result in a situation, as Dr. Altglas seems to agree, in which, due to a context of “religious deregulation in modern societies,” as she puts it, “a dimension of choice and diversity” becomes a relevant factor in analyzing the types of constraints on, as well as, I would add, the types of empowerments toward, bricolage that are present in this kind of institutionally deregulated social environment

A Further Appeal to the Individual as a Relevant Level of Analysis

This response, then, is not so much a defense of the scholarly value of the concept of bricolage, as I am not particularly invested in its use. This is, however, a defense of the academic interest in the individual, which I take to be inclusive of the variety of ways that the activities of individuals are constrained, or not, in any given context. It is an insistence that all macro-scale social phenomena are composed of a large number of micro-scale processes among individual humans. To that degree, it is important to notice that while, indeed, all acts of bricolage are constrained, they are certainly not all equally constrained and, indeed, some contexts may encourage bricolage while others might act, relatively speaking, to diminish its occurrence. There are always, in any act of cultural improvisation, a unique array of factors which go into determining whether any particular representation will be chosen as the tool for a particular job at a particular time by a particular individual. However, Altglas’ analysis would seem to overemphasize the importance of external, social factors and, as a result, downplays other significant, internal, cognitive factors that are inevitably in play during any act of bricolage. Indeed, Dan Sperber has emphasized that,

“[t]hough which factors will contribute to the explanation of a particular strain of representations cannot be decided in advance, in every case, some of the factors to be considered will be psychological, and some will be environmental or ecological (taking the environment to begin at the individual organism’s nerve endings and to include, for each organism, all the organisms it interacts with)” (Sperber 1996, 84).

To the extent that it is, indeed, true that scholars have tended to ignore what Sperber calls the environmental or ecological factors that influence the reception, retention, and further conceptual utilization of available cultural representations, Altglas’ attempt to bring environmental factors, such as nationality or economic class, back into focus is an important correction to an analytic oversight. It is also important, however, to insist that she be careful not to pull too far in the other direction toward an equally lopsided type of analysis which leaves the mental or psychological factors largely unconsidered. Since, as Sperber notes, both will be present in every case, when a potential bricoleur encounters a cultural representation, both psychological and environmental factors need to be considered when analyzing constraints on, and empowerments toward, the utilization of that representation for an act of bricolage.

“Potentially pertinent psychological factors include the ease with which a particular representation can be memorized, the existence of background knowledge in relationship to which the representation is relevant, and a motivation to communicate the content of the representation. Ecological factors, include the recurrence of situations in which the representation gives rise to, or contributes to, appropriate action, the availability of external memory stores (writing in particular), and the existence of institutions engaged in the transmission of the representation” (Sperber 1996, 84).

But, where does that leave us? To my reading, it leaves us with quite a wide spectrum of potential degrees of constraint on the abilities of individuals to pick and mix cultural representations. Are there some contexts in which such constraints are more oppressive toward innovation than others? Are there, on the contrary, some contexts in which interpretive freedom is relatively more unconstrained? Does the relevant question, then, become not simply ‘when is bricolage taking place’, but, rather, to what degree is the density and regularity of the practice of bricolage itself encouraged or constrained by different psycho-socio-cultural contexts?

Individualism and Organizations: On the Selection of Case Studies

I will look forward with anticipation toward the studies that Altglas has signaled that she is interested in pursuing in the future. I think that analyses of “bricolage in more conservative religious settings” or in “in messianic congregations” might provide important accounts of exactly to what degree institutional settings might constrain (or even empower) certain acts of bricolage. I would argue, however, that ultimately, as important as such studies will inevitably be, they cannot adequately address the question that Altglas most seems to want to address, which is the issue of religious individualism. I fear that in her eagerness to debunk Sheilaism, Altglas has failed to select representative case studies for her analysis. Given an attempt to investigate radical individualism, the choice to undertake that examination through the sociological analysis of religious organizations (Altglas’ study is based on fieldwork among Siddha Yoga and Sivananda Centers and the Kabbalah Center) that are rooted in particular cultural traditions would seem to obviate any serious chance at arriving at the desired conclusions. It is simply an analysis of the wrong data. In the introduction to her book, Altglas attempts to account for this oversight but, ultimately, her mea culpa does not overcome the problem.

“The readers might wonder why these case studies in particular have been selected. For a start, new religious movements (NRMs), as circumscribed groups with a specific teaching, represent good settings to the production and appropriation of religious resources. These processes in less ‘formative’ (Wood 2009) environments, such as those designated New Age, are more diffuse and therefore less easy to study” (Altglas 2014, 19).

In other words, the very populations that would be most appropriate to a study of religious individualism are here claimed to be too difficult to study, precisely because they are so individualistic and lack a central organizational hub from which to launch the study. Now, don’t get me wrong, as someone who spends his time studying these ‘non-formative’ communities of discourse, I am well aware that what she says is true. It can certainly be much more difficult to systematically study a decentralized milieu than to study a centrally-organized group with a more clearly delineated membership (though it certainly need not be inherently more difficult to do so—I’m quite sure that I’ve had more success with analyzing many of my decentered populations of interest than others have had getting access to, for instance, the inner realms of Scientology). For those of us who have spent quite a lot of time and effort investigating such ‘non-formative’ milieus, however, Altglas’ justification for her selection of case studies is not likely to be satisfying, when we note that the materials that we specialize in are shrugged off so effortlessly, as though that omission were, in the end, unlikely to actually inform the conclusions drawn from the study. In that sense, Altglas has provided us a particularly intriguing analysis of the of the constraints on activities of bricolage among members of the movements that she has studied, but, in order to corroborate her broader arguments against considerations of more radically individual combinatory practices, a study is still needed of the right kinds of case studies to address those issues, and that has not been accomplished here.

This discrepancy becomes clear in some of Altglas’ comments during the interview. For instance, she describes a potential bricoleur “doing a bit of yoga and then, perhaps, after two or three years, deciding that meditation is better.” This hardly sounds like the kind of highly individualized bricolage that we would be interested in so much as it appears to be an instance of serial participation in different activities. This seems miles apart from the types of improvisational cultural combinations that I would want to study in terms of bricolage or anything that might be considered a pronounced variety of individualism. If we really want to look at the types of bricolage that many of the scholars that Altglas critiques are actually interested in, we’d want to look at people creating websites which lay out their beliefs that link, for instance, Jesus’ last words on the cross, the Mayan calendar, Atlantis, Freemasonry, the electric telegraph, Vedic astrology, UFOs, the secret government, the Galactic Federation of Light, and the psychoactive properties of the pineal gland into some sort of ‘cohesive’ narrative that makes sense to them (at some point in time). There are millions of people like this out there in the world who don’t actively participate in centrally-organized religious communities, who don’t have a local group of peers to share metaphysical discourse with, and who develop their views primarily through reading books, participating in online forums, listening to music, watching YouTube, and the like. These individuals, too, are, of course, not unlimited in their improvisational capabilities. They also only have certain cultural resources available to them. They exist in a certain kind of society that instills certain kinds of values. Nonetheless, many of these individuals are significantly less constrained in their acts of bricolage than many others who explore religious themes only in the context of an established community or from within a particularly restrictive national setting (e.g. North Korea). Indeed, many of these individuals exist in social contexts that actually empower them to participate in copious acts of bricolage. The outlook of the Perennial Philosophy, in particular, which sees all religious traditions as equally fair game for religious inspiration as they are all taken as access points to a single, universal truth, dominates contemporary alternative spirituality, and, in many ways, actually demands those who adopt such a viewpoint to become rampant bricoleurs. While these modern bricoleurs still face very real and very important constraints, it is pertinent for scholars to take note of the ways in which their acts of bricolage are undertaken in a more highly individualized manner than is common in many more traditional, institutional religious settings. The question then should not be simply whether or not individuals are free or constrained in their combinatory endeavors, but rather how free or constrained they are in any given context and, thus, precisely how individualistic they are being. In the final analysis, all constraints are certainly not equal.

References

Altglas, Veronique. 2014. From Yoga to Kabbalah: Religious Exoticism and the Logics of Bricolage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luckmann, Thomas. 1979. “The Structural Conditions of Religious Consciousness in Modern Societies.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 6, pp. 121-137.

Sperber, Dan. 1996. Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.