In his recent RSP interview, Dr. Robert McCauley provides a brilliant overview of some of the founding philosophical principles that have been a foundation for the study of religion. Dr. McCauley has been known as one of the key founders of the “Cognitive Science of Religion” (CSR) since he co-authored the book “Rethinking Religion” (Lawson & McCauley, 1990); ever since then he has guided the field with a keen understanding of the empirical, philosophical, and socio-cultural literature from which CSR draws.

In the interview, he touches on an aspect of the scientific study of religion that I would like to highlight: explanatory pluralism. I want to use this opportunity to offer a critical review of CSR in light of explanatory pluralism. It is my belief that the failure of CSR to adequately address its inherently interdisciplinary nature has been a detriment to the field and that by addressing these issues it will help the field to grow as well as to help non-CSR specialists understand more of the subtlety of this scientific approach to our subject. I, by no means, think I can settle the issues in the space here, but I would like to use Dr. McCauley’s interview as a springboard from which a discussion can be launched.

Explanatory pluralism

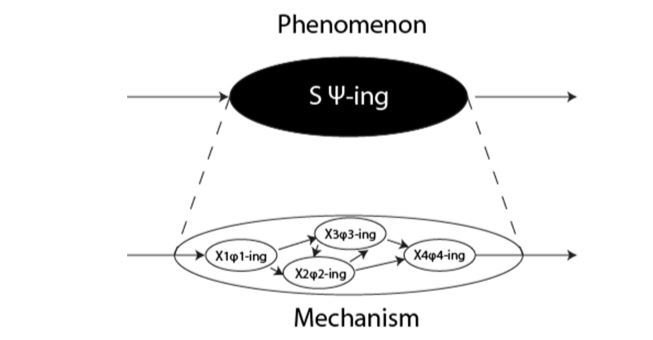

The primary aspect of the interview that I’d like to address is McCauley’s concept of “explanatory pluralism,” which holds that a phenomenon can be explained at different levels of inquiry. The explanatory pluralist maintains that there is no such thing as a final, full, or complete explanation and that each analytical level in science has tools and insights that can be brought to bear on any phenomenon of interest, including religion.

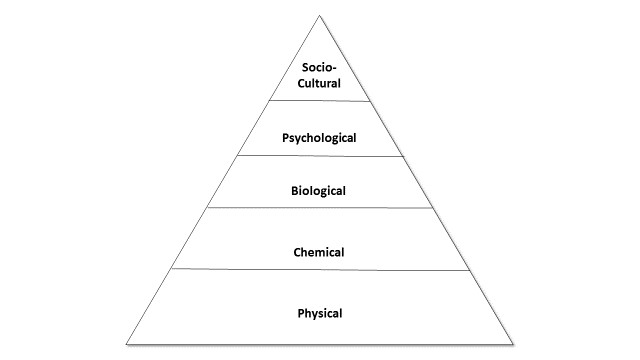

He notes that there are “families” of sciences, and these should probably not be taken as strong demarcations between fields. He also notes that this presumes a hierarchy whereby all events at one level are events of the level beneath it. For example, all events that are chemical events are physical events, but not all physical events are chemical events. McCauley did not explicitly state the “chemical sciences” as a family, but I have added it here since it is hard to imagine a biological event that isn’t chemical but we can imagine chemical events that aren’t biological (e.g. fire or Diet Coke and Mentos).

Critique

Here, my critique is that this sort of explanatory pluralism is really only useful as a framework for constructing an interdisciplinary research project, aimed at understanding some phenomenon like religion, if there is theoretical continuity between the sciences being employed to explain a phenomenon.

Skipping levels in reductive sciences

First, it is hard to imagine a scenario where one should “skip” a level of his pyramid. Explaining socio-cultural phenomena exclusively at the level of biology misses the fact that any biological effects on culture or religion would be mediated by psychology. The endless debate of Nature vs. Nurture settled that one cannot reduce religion to our genes alone. However, our psychological capacities seem to have evolved, and these capacities do give rise to religion. So it is not to say that biology isn’t important (to the contrary); it is just that solely-biological explanations of religion are hollow when neglecting how it is that socio-cultural phenomena (like religion) are affected by psychology.

Theoretical continuity

Second, the theories being employed must have compatible axiomatic assumptions. If assumptions of one theory, which is used to explain some target phenomenon, violate the assumptions of another theory used to explain the same phenomenon at a different level there is an incongruity.

Think of it this way, if we are adding two numbers, X and Y, to get Z as an answer and there are equal assumptions about X and Y then the answers are clear; example: 6 + 6 = 12. However, if the theory from which we assess X and Y is not equal to the theory from which we assess z (i.e. the theory has asymmetrical assumptions), then the equation is not so simple and it is possible that 6 + 6 ≠ 12. To use a mathematical example, 6 plus 6 equals 12 (6 + 6 = 12) in our number system, which is based on the assumption of having a base of 10. However, in a senary number theory (base-6), the answer to our equation is 20 in base-10.[1] Without going deeper into number theory, suffice to say that this equation is not valid as we are adding variables from one theory in search of an answer in another theory. This creates an issue when we see a target phenomenon “Z” and hope to explain it in terms of lower level properties, when our theories don’t align.

Complexity and reductionism in religion: Down the rabbit hole

This complication is spelled out quite clearly in mathematics, but may be more complex when looking at socio-cognitive systems like religious systems (or political systems, or economic systems). One of the reasons that this is complex is because the interactions at one level may not be directly reducible to the parts that it is built upon at a lower level; colloquially, it is greater than the sum of its parts.

Here I would like to address a crucial issue in the study of religion, that of emergence. If something is “emergent” it is said to be greater than the sum of its parts. Emergence comes in two forms, strong and weak. Strong emergence is the stance that a phenomenon—observed at one level—cannot be reduced, even in principle, to the laws specified at a lower level. Weak emergence is the stance that a phenomenon is the result of interactions at a lower level, but the target phenomenon is not expected given the interactions at this lower level.

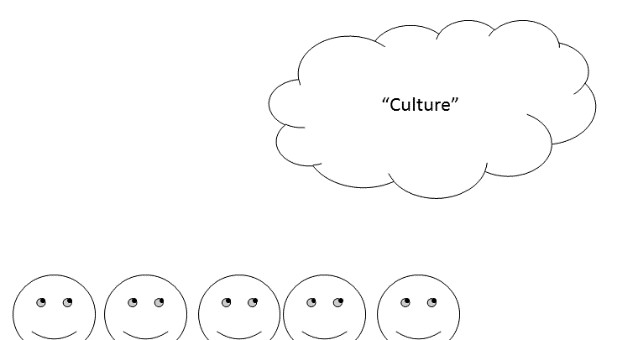

Many people hold that religion is an emergent phenomenon that cannot be reduced. These discussions are complex and a review of this literature is far beyond the scope of this response. However, let us just imagine how an interdisciplinary approach to religion, as an emergent phenomenon, could arise from lower level properties. Now, this assumes that religion is weakly emergent. First, because strong emergence is incompatible with scientific reductionism and is better fit for interpretive paradigms that seek to explain the social at the level of the social (ala Durkheim); I’ll address the idea that religion may be a causal force in just a moment. However, if we move beyond that—even if only for the sake of argument—religion must arise from some lower level properties.

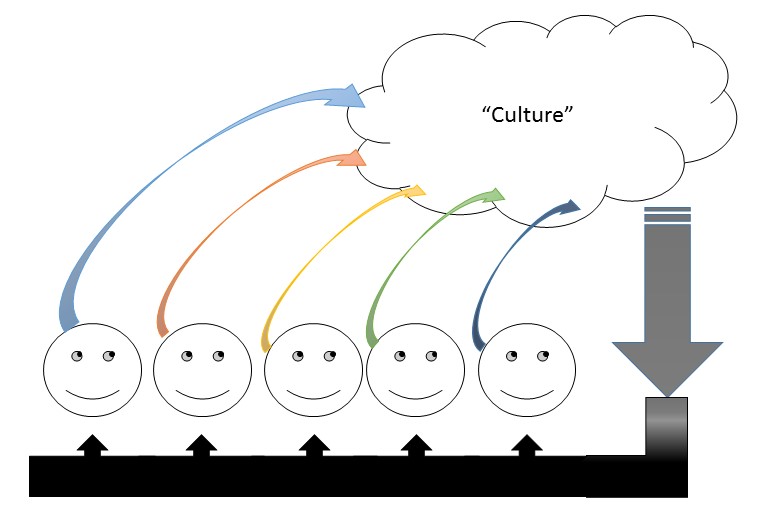

So, to exemplify this, I’m going to use a very elementary analogy. Let’s return back to the “Pyramid of Science” above. If something at the cultural level is emergent in the strong sense, it means that there is no connection to the laws at the lower (i.e. psychological level). It is an unconnected cloud floating above the minds of people.

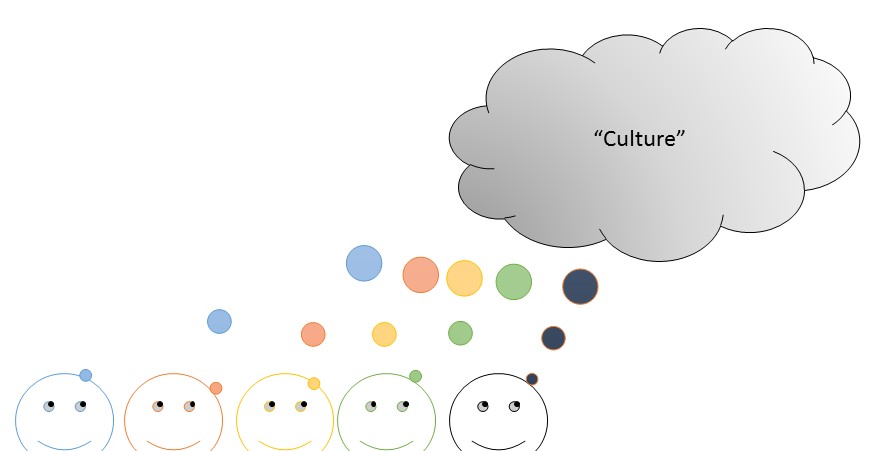

This approach is in many ways black and white. Culture is not directly connected to the rules that are followed by its constituent parts. Most individuals in the scientific study of religion (SSR) reject this claim because if one imagines a world without people we simply would not have culture. Therefore, there is posited to be some connection between “Culture” and the minds of individuals that hold, sustain, and generate that culture. This position is more in line with the weak emergent perspective. This holds that culture is not directly reducible to the lower-level laws of human psychology, but there is some connection. The current scientific explanation for culture and religion is that it is “generated” by the collective minds of all the individuals in a group. This allows for culture to have the shades of grey that result from all the colorful cognitive machinery with which humans are endowed.

Now, one might ask: “Wait, this is too simple, why is it that different cultural groups behave differently?” Within complexity theory, emergent phenomenon can exert causal forces. Some even believe that no higher-level entity can change without exerting some force on its lower level parts (for a deeper discussion on emergentism see Kim, 1999); that is to say, within a complex systems perspective, culture can shape people, and people generate religion and culture.

What this has to do with religion: Taking the red pill[2]

Now, at this point in the rabbit hole, you may be wondering if I’ve gone off the rails. Well, yes, but only to exemplify an important point concerning how modern cognitive science has surpassed CSR and what religious studies could serve to learn from it.

Above, I outline a constant, complex, feedback syste m whereby culture emerges from the complex interactions between humans’ mental facilities, and in turn, creates an environment within which these individuals live. This environmental input, indifferentiable from the plants, animals, and water, is an important aspect of the environment and therefore can appear to cause individuals to do things just as the presence of a snake would cause a person to jump. This feedback system is—in principle—not unlike the physical systems that cause guitars to screech when too close to an amp. One (culture) arises from the minds of interacting people, which are, in turn, affected by that culture. Furthermore, we can visualize them with our “culture cloud” like so:

m whereby culture emerges from the complex interactions between humans’ mental facilities, and in turn, creates an environment within which these individuals live. This environmental input, indifferentiable from the plants, animals, and water, is an important aspect of the environment and therefore can appear to cause individuals to do things just as the presence of a snake would cause a person to jump. This feedback system is—in principle—not unlike the physical systems that cause guitars to screech when too close to an amp. One (culture) arises from the minds of interacting people, which are, in turn, affected by that culture. Furthermore, we can visualize them with our “culture cloud” like so:

Now, in order to understand this complex system, we have to hold the way in which we measure everything steady between the psychological level and the socio-cultural level. We wouldn’t want to use the metric system for one thing and the imperial system for another. Although it may seem like things are stable at first glance, such incongruity will not result in a viable approach to theory building. Furthermore, we need to change the way we approach measuring religion. Saying something is complex is no longer a viable excuse to say we cannot study it empirically. Complex statistics from recursion analysis (Lang, Krátký, Shaver, Jerotijević, & Xygalatas, 2015) to network analysis (Lane, 2015) allow us to discern non-linear patterns in the study of religion. Also, computer models are allowing us to study these relationships as well (see Bainbridge, 2006; Braxton, 2008; McCorkle & Lane, 2012; Shults et al., Submitted; Upal, 2005; Whitehouse, Kahn, Hochberg, & Bryson, 2012; Wildman & Sosis, 2011).

Conclusion

Many of those in the scientific study of religion argue that “culture” or “religion” is a causal force. This has led some in the scientific study of religion to ignore the great scholarship of religious scholars who acknowledge that religion is an academic abstraction invented by western intellectuals (Smith, 2004)—at times even leading those scientists of religion to implicitly treat religion as a sui generis phenomenon. However, by abandoning our linear thinking (and statistics!) we could start to investigate religion as emergent and not simply the additive “sum” of the constituent minds of people. Rather, we can look at it for what it is, the result of iterations of interactions among individuals in complex socio-biological environments (i.e. contexts) that is instantiated in an ever-recursive system between the cognitive and socio-cultural levels of analysis. As I hope it is plain to see, I wholly support Dr. McCauley’s commitment to explanatory pluralism. I only argue that we be more mindful of the theoretical continuity which is necessary to produce valid models[3] of religion.

References

Bainbridge, W. S. (2006). God from the Machine: Artificial Intelligence Models of religious Cognition. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Braxton, D. M. (2008). Modeling the McCauley-Lawson Theory of Ritual Forms. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University.

Kim, J. (1999). Making Sense of Emergence. Philosophical Studies, 95(1-2), 3–36. Retrieved from http://www.zeww.uni-hannover.de/Kim_Making Sense Emergence.1999.pdf

Lane, J. E. (2015). Semantic Network Mapping of Religious Material. Journal for Cognitive Processing. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-015-0649-1

Lang, M., Krátký, J., Shaver, J. H., Jerotijević, D., & Xygalatas, D. (2015). Effects of Anxiety on Spontaneous Ritualized Behavior. Current Biology, 1–6. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.049

Lawson, E. T., & McCauley, R. N. (1990). Rethinking Religion: Connecting Cognition and Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McCorkle, W. W., & Lane, J. E. (2012). Ancestors in the simulation machine: measuring the transmission and oscillation of religiosity in computer modeling. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 2(3), 215–218. http://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2012.703454

Shults, F. L., Lane, J. E., Lynch, C., Padilla, J., Mancha, R., Diallo, S., & Wildman, W. J. (n.d.). Modeling Terror Management Theory: A computer simulation of hte impact of mortality salience on religiosity. Religion, Brain & Behavior.

Smith, J. Z. (2004). Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Upal, M. A. (2005). Simulating the Emergence of New Religious Movements. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 8(1). Retrieved from http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/8/1/6.html

Whitehouse, H., Kahn, K., Hochberg, M. E., & Bryson, J. J. (2012). The role for simulations in theory construction for the social sciences: case studies concerning Divergent Modes of Religiosity. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 2(3), 182–201. http://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2012.691033

Wildman, W. J., & Sosis, R. (2011). Stability of Groups with Costly Beliefs and Practices. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 14(3).

[1] Interested readers can go check out online conversion tools that will convert numbers with different bases, such as that found here: http://www.unitconversion.org/unit_converter/numbers.html

[2] For those unfamiliar with the movie “The Matrix”, this is explained here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_pill_and_blue_pill

[3] I mean this in the conceptual and computational sense, including scholars of religion engaged in philosophical, historical, and empirical endeavors.