Dr. Gabor Klaniczay has illuminated many of the issues related to stigmata in the nineteenth and twentieth century, focusing on Italy—which seems especially susceptible to miracles of all kinds—and on both Catholic and Protestant commentary on the nature and significance of stigmata. Careful to acknowledge contrary opinions and claims, he also explains that Catholic doctors were inclined to credit stigmatics and their wounds as proof of the supernatural, while Protestant doctors were more critical and prone to deny this significance, attributing the conditions to psycho-somatic conditions or fraud.

The nineteenth- and twentieth-century debates on these issues animated people of faith, religious leaders and medical practitioners as well, and the debates took place in a context that historians have described as increasingly secular, as the Enlightenment, the so-called Age of Reason, proceeded into the nineteenth century. Amidst the pattern of secularization, historians such as Michel de Certeau have also noted the localized energies of Catholic revivals and their social context in which mystical experience met political motivations and religious authorities.

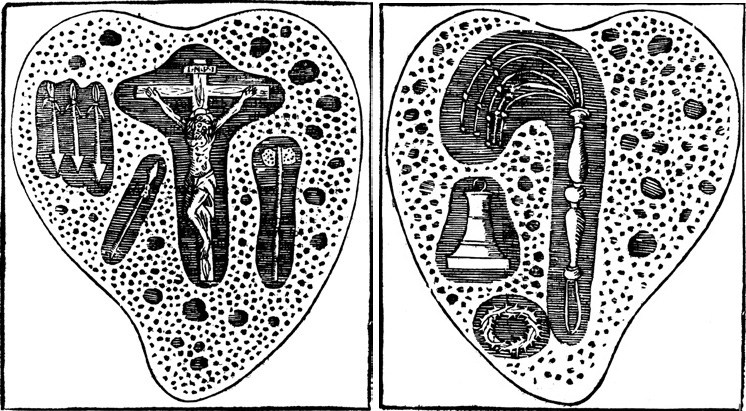

As this description of a long historical moment may suggest, signs of sanctity remain contested; their significance seems always slightly more open to interpretation, diagnosis, even narrative than we would imagine or than some would hope. This openness or over-abundance of potential significance has a long history, and if we follow it carefully, some of its main threads emerge as early as the 1300s when nuns’ bodies were opened, after death (post-mortem), to assess their internal anatomy for potential signs of sanctity. The context was canonization in which these bodily phenomena were used as evidence. For example, Chiara of Montefalco (1268-1308) was an Augustinian nun; and when she died, her sisters dissected her corpse and found, in her heart, a small cross, a lance, a crown of thorns, and other instruments of the passion of Christ, and in her gall bladder, three stones. Her sisters “saw” these signs as signs of her sanctity, while a local Franciscan argued they had placed the items there in the course of the autopsy. The argument was not resolved; it resurfaced again when a publisher in the 1650s printed images of Chiara’s heart, woodcuts featuring the anatomical abnormalities. Inquisitors, operating under the constraints and concerns of the Counter Reformation, were worried that the images like the abnormalities were not “authentic” (Bouley). But the concern, as Bradford Bouley has explained, was different in the 1650s because the medical tradition by that time had embraced the work of Galen, including his anatomical studies, which were clearly evoked in the arguments about the inauthenticity of Chiara’s cardiac abnormalities.

Dr. Gabor Klaniczay has illuminated many of the issues related to stigmata in the nineteenth and twentieth century, focusing on Italy—which seems especially susceptible to miracles of all kinds—and on both Catholic and Protestant commentary on the nature and significance of stigmata. Careful to acknowledge contrary opinions and claims, he also explains that Catholic doctors were inclined to credit stigmatics and their wounds as proof of the supernatural, while Protestant doctors were more critical and prone to deny this significance, attributing the conditions to psycho-somatic conditions or fraud.

The nineteenth- and twentieth-century debates on these issues animated people of faith, religious leaders and medical practitioners as well, and the debates took place in a context that historians have described as increasingly secular, as the Enlightenment, the so-called Age of Reason, proceeded into the nineteenth century. Amidst the pattern of secularization, historians such as Michel de Certeau have also noted the localized energies of Catholic revivals and their social context in which mystical experience met political motivations and religious authorities.

As this description of a long historical moment may suggest, signs of sanctity remain contested; their significance seems always slightly more open to interpretation, diagnosis, even narrative than we would imagine or than some would hope. This openness or over-abundance of potential significance has a long history, and if we follow it carefully, some of its main threads emerge as early as the 1300s when nuns’ bodies were opened, after death (post-mortem), to assess their internal anatomy for potential signs of sanctity. The context was canonization in which these bodily phenomena were used as evidence. For example, Chiara of Montefalco (1268-1308) was an Augustinian nun; and when she died, her sisters dissected her corpse and found, in her heart, a small cross, a lance, a crown of thorns, and other instruments of the passion of Christ, and in her gall bladder, three stones. Her sisters “saw” these signs as signs of her sanctity, while a local Franciscan argued they had placed the items there in the course of the autopsy. The argument was not resolved; it resurfaced again when a publisher in the 1650s printed images of Chiara’s heart, woodcuts featuring the anatomical abnormalities. Inquisitors, operating under the constraints and concerns of the Counter Reformation, were worried that the images like the abnormalities were not “authentic” (Bouley). But the concern, as Bradford Bouley has explained, was different in the 1650s because the medical tradition by that time had embraced the work of Galen, including his anatomical studies, which were clearly evoked in the arguments about the inauthenticity of Chiara’s cardiac abnormalities.

As a particularly dramatic account in the early history of signs and sanctity, this episode highlights the importance of context, for we see how the local context of Chiara served to establish claims to sanctity in the early 1300s and how the more extensive context of the Counter Reformation generated an overlapping but ultimately different set of debates about those same signs in the 1650s. The case of Chiara also invites us to reflect on the entanglement of religion and medicine, a thread in this longer history that persists even to today. As Dr. Klaniczay discussed at the end of his interview, the stigmata of Padre Pio were studied and debated within the Church, amidst local and more extensive concerns, and they involved the testimony of medical practitioners, especially in this case, a pharmacist.

In earlier cases where bodily signs of sanctity were being established and evaluated, it became routine for medical practitioners to participate. This thread began to materialize, as it were, in the discussions of signs that potentially fell into the category of “supernatural” or beyond nature rather than anatomical abnormalities that were considered contrary to nature, mistakes of nature or abnormalities that happened once in a blue moon, such as hermaphroditic anatomies. Physicians and anatomists were supposed to be expert in the latter. The most robust period of development for this taxonomy and for the evaluation of signs of sanctity was probably the Counter Reformation era, which may be said to begin with the formation of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). As Bouley acknowledges, in its first 100 years, ca. 1550-1650, the Counter-Reform Catholic church ordered the posthumous examination of almost every prospective saint. Examinations required medical professionals to evaluate anatomical abnormalities—effectively categorize them as either supernaturam or contra naturam—and these included unusual anatomy, miraculous incorruption (the corpse’s perceived lack of decay), and evidence of extreme asceticism (Bouley 2-3). These examinations developed formal practices, empirical understandings of the body, standards of evidence, and other technical formulations that granted legitimacy to the proceedings. Indeed, postmortems of Church officials became routine by the 1700s. The Catholic church, to borrow Bouley’s phrase, formed an alliance with anatomical studies; and all subsequent promoters and detractors relied on it as they argued about the significance of stigmata and other bodily phenomena in holy bodies.

One additional thread that you might investigate in this long history is gender, for female bodies were central to it. In addition to general resources, some of the works listed below use the lens of gender to discover unusual and expected details and contours of this history. Katharine Park and Gianna Pomata, in the sources listed below, reflect on how the practices of autopsy and the holy bodies of women perpetuated or disrupted gendered ideas about sanctity and hierarchies of authority, evidence, and saints. Continuing this line of inquiry, Bouley explains that postmortems during the Counter Reformation inscribed a conservative gender hierarchy, establishing the Church’s authority in opposition to feminine weakness—holy women, who had adopted a masculine set of markers in their public life, were overtly sexualized and feminized after death in a process that subordinated them more effectively to eccelsiastical authority. Male bodies, Bouley continues, were made asexual and hypermasculine after death. Anatomy was designed, quite literally, to fit one’s destiny.

Resources:

Elisa Andretta, “Anatomie du Venerable dans la Rome de la Contre-reforme. Les autopsies d’Ignace de Loyola et de Philippe Neri,” in Conflicting Duties: Science,

Medicine and Relgion in Rome, 1550-1750 (Warburg Institute, 2009), 255-280.

Bradford Bouley, Pious Postmortems: Anatomy, Sanctity, and the Catholic Church in Early Modern Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

Piero Camporesi, The Incorruptible Flesh: Bodily Mutation and Mortification in Religion and Folklore, trans. Tania Croft-Murray (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Jacalyn Duffin, Medical Miracles: Doctors, Saints, and Healing in the Modern World (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Katharine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (Zone Books, 2006).

Gianna Pomota, “Malpighi and the Holy Body: Medical Experts and Miraculous Evidence in Seventeenth-Century Italy” in Renaissance Studies 21, no. 4 (2007): 568-586.