- A response to the podcast “Melodies of Change: Music and Progressive Judaism”

- By Judah Cohen, PhD, Indiana University Bloomington

- I began writing this response on the day before Thanksgiving, and the day after the conclusion of the American Academy of Religion (AAR)’s 2018 meeting in Denver. My colleagues Monique Ingalls, Alisha L. Jones, and Zöe Sherinian all attended AAR, jetting over from the Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM)’s more intimate (c. 1000 attendees) annual meeting the day before. I did not. The last time I attended AAR, in 2006, I felt overwhelmed by bigness, unsure how to go beyond my small disciplinary circle in a scholarly sea of logocentrism. While I sought out like-minded colleagues, I found, like Illman, a significant center of scholarship oriented around the arts as an adornment to worship, rather than as a core part of it. In the exhibit hall, meanwhile, music seemed to be the domain of media companies presenting their latest (typically Christian) worship technologies. Finding a place for music in the already huge conference felt particularly fraught to me.

- How much has changed by 2018? A quick perusal of the AAR/SBL program shows four sessions on music out of about twelve hundred organized events. I admire my ethnomusicology colleagues’ initiative and energy—in their own Society they have successfully organized a thriving Section on Music, Religion and Sound; and Jonathan Dueck and Suzel Reily’s recently published Oxford Handbook of Music and World Christianities received recognition as an outstanding collection of essays. Yet connecting this approach to the core concerns of Religious Studies remains a daunting affair.

- So thank you, Ruth Illman.

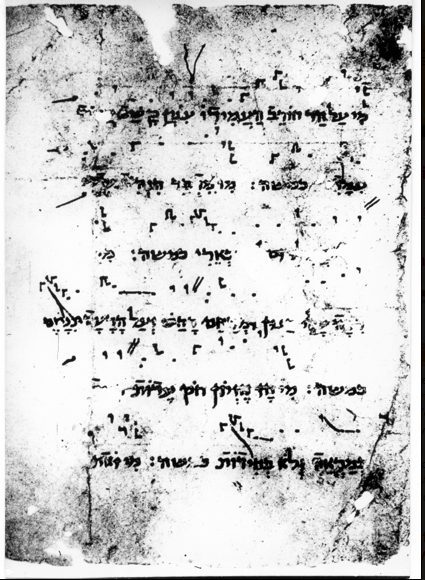

Above, Obadiah the Proselyte (early 12th century): manuscript for the liturgical poem “Mi Al Har Morev.”

- The book that inspired Dr. Illman’s podcast offers a meaningful model for bridging Ethnomusicology and Religion as mature scholarly disciplines. Citing Rosalind I. J. Hackett, and channeling assertions by Isaac Weiner and others, Illman seeks to restore to Religious Studies the soundtrack that has long made worship and liturgy viable, both publicly and (sometimes) privately:

“We need to realize that music, and the arts in general, are not just ornaments or illustrations of something more profoundly important to religion, but they are aspects of religious engagement in their own right that we need actively to give serious scholarly attention.”

- Illman’s assertion can sound like a challenge to a field where text’s inherent physicality gives it a privileged place: where the very act of reading, writing or printing not only preserves a record, but can sacralize a ritual. Text conveniently symbolizes the multisensory experience of spirituality and tradition, which we describe and ritualize in the process of projecting a broader experience of the numinous. But what happens if we enter the experience directly through music—in a sense turning music into the center of focus, with text as an auxiliary? It’s more than a thought experiment: as Illman points out, drawing on decades of work in ethnomusicology to support her, people regularly give sound more weight than text as a determinant of religious tradition and authenticity. The view holds in different ways across faith traditions. Liberal populations might at first seem the most likely to observe here, due to (often biased) perceptions that they interpret core religious texts less literally than more “orthodox” groups. Yet music can also be a powerful lens of authenticity even in those populations: in Judaism, for example, we can see such issues in the nigunim (melodies) of Hasidic populations, the Lernensteiger melodies used to teach rabbinic texts (as studied by Lionel Wohlberger), and the universal dilemmas of melody choice, timbre, and sound production that pervade many forms of worship.

- Indeed, public prayer frequently shifts into musical primacy, as anyone who has attempted to decipher the words of a polyphonic Mass in a cathedral (including Church officials!) might recognize. Music forcefully reminds us of religion’s timebound nature and holds its own systems of rhythm and inflection—as I tell my students, you cannot skim music the way you can cram a text. And the more closely we look into the topic, the more deeply we can notice how congregants bring to a complex and sophisticated palette of descriptors and tastes to the music they experience in their spiritual lives. We hear these descriptors regularly, as Illman shows in her larger study, and as Jeffrey Summit has explored in his book The Lord’s Song in a Strange Land. Liturgical music jobs are won and lost by them. And the “worship wars”—disputes between the music of “high” and “low” culture—show how crucial they are to the worship experience (as illustrated by several selections in Routledge’s recent Congregational Music Studies Series).

<

p style=”text-align: center;”>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fcTneBjgaA8

Above, a Friday evening service during Chanukah 2014 at B’nai Jeshurun Synagogue in New York City, known for at least 25 years now for its musical services.

- Entering scholarly discussions of religion through music can thus open new perspectives for understanding communal spiritual dynamics and normalize the idea that populations can be spiritually articulate even when they identify only loosely (or symbolically) with core texts —allowing us to move beyond moralistic critiques of “losing touch” with tradition that pervade both scholarship and practice.

- Illman’s description of authenticity as described through her contemporary interlocutors’ musical experiences can also extend to broader discourses of authority, including debates over the performance of sacred text and the role of music (and by extension other arts) in conferring spiritual authority. Whether through Quran recitation contests, the training of Jewish cantors, mantra chanting, or the long parallel development of music and text in various Christian denominations, music and text depend on each other for their continued vitality. In my own research on both contemporary liturgies and the American Jewish nineteenth century, I found music to be more than just a liturgical enhancement: it made sacred text viable, connecting the often obtuse and generalized words with congregants’ personal needs and cultural norms.

- When it comes to music, then, Illman’s study offers an excellent opportunity to see how ethno/musicologists can bring greater depth to the study of religion—and particularly how their/our methods can enhance historical debates around the status of text. David Stern, among a growing number of scholars, now highlights physical and textual mutability as a central part of what we consider textual “tradition.” What greater depth we can find, then, when we restore sound to the experience and think of text as a contributor to a crowded and rich sensory view of the numinous—while seeing other modes of expression as equally rich doors into our intellectual discussions.

Suggested Reading (at least as a start):

- Judah M. Cohen, Jewish Religious Music in Nineteenth Century America: Restoring the Synagogue Soundtrack (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, forthcoming April 2019).

- Jonathan Dueck and Suzel Ana Reily, The Oxford Handbook of Music and World Christianities (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Rosalind I. J. Hackett, “Sound, Music, and the Study of Religion.” Temenos 48, 1 (2012), 11-27.

- Monique Ingalls, Singing in the Congregation: How Contemporary Worship Music Forms Evangelical Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Deborah R. Justice, “The Curious Longevity of the Traditional–Contemporary Divide: Mainline Musical Choices in Post–Worship War America,” Liturgy 32, 1 (2017), 16-23.

- Mark L. Kligman, Maqām and Liturgy : Ritual, Music, and Aesthetics of Syrian Jews in Brooklyn (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009).

- Ellen Koskoff, Music in Libavitcher Life (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001).

- Anna Nekola and Tom Wagner, eds. Congregational Music Making and Community in a Mediated Age. (New York: Routledge, 2015).

- Zoe Sherinian, Tamil Folk Music as Dalit Liberation Theology (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014).

- David Stern, The Jewish Bible: A Material History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017).

- Jeffrey Summit, The Lord’s Song in a Strange Land: Music and Identity in Contemporary Jewish Worship (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Jeffrey Summit, Singing God’s Words: The Performance of Bible Chant in Contemporary Judaism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Isaac Weiner, Religion Out Loud: Religious Sounds, Public Space, and American Pluralism (New York: NYU Press, 2014).

- Lionel Wolberger, “The Music of Holy Argument: The Ethnomusicology of a Talmud Study Session,” Studies in Contemporary Jewry IX (1993), 110-138.