“The Secret Life of Scriptures: Black Scriptures as Tending to New Afro-Futures”

Responding to “Roots as Scriptures, Scriptures as Roots”

IU School of Liberal Arts at IUPUI

The “secret” behind scriptures is that they don’t have to be read or understood or even significantly engaged by a community in order to be imagined and used as a sacred text. It is the legacy beyond, between, and surrounding the text or scripture that matters. Dr. Richard Newton powerfully makes this claim on the “Religious Studies Project” podcast, and I would like to argue that scripture-making, as he engages in his discussion of the canonical text Roots, is central to democracy and specifically Black communities’ engagement with and resistance to certain aspects of the democratic project. Roots is a Black scripture not simply because it is a powerful text in the Black community, but because it is about the creation of the Black subject. Scriptural projects not only activate ways of knowing the world, but more importantly they activate ways of being in the world. Scriptures provide a new orientation or what might be thought of as a creation story, or at least containing aspects of an origin myth. Black scriptures don’t just tell the story and myths of Black beginnings or civilizations, but they create the possibility of Black humanity and subjectivity in an anti-Black world. Scriptures have existed for a long time, but I am arguing for an understanding of Black scripture that emerges and has particular and peculiar relevance in the long shadow of white supremacy and the modern world. The significance of these modern scriptural projects is that they provide new apertures for belonging and futures, especially amongst its most marginalized subjects (see the pioneering work of Vincent Wimbush for additional discussion).

Alex Haley’s Roots, albeit canonical and critical to understanding the Black public sphere of the latter half of the 20th century, is a particular foundational story. I agree that it was consumed vociferously amongst a variety of black and white demographic sectors. However, it is primarily a scripture for Black middle-class mobility and subjectivity. The story of Roots is about rooting the Black subject in the project of mobility and respectability that is essentially routed through the modern categories of neo-liberal capitalism. Haley, in this regard, is both a griot or modern African storyteller as well as the leader of a mega-church phenomenon. Haley created a scriptural project that pays homage to Africa, the ancestors, and the horror of the middle passage, but the salvation that his scripture offers is not easily accessible to the majority of the Black community.

Especially, in the middle of the 1970s, Haley’s method of recovering his heritage was relatively unavailable to most African Americans who wanted to trace their roots. Their only option was to take comfort or to be rooted in the story of the idealized or exceptional stories of those who have access or connection to Africa. Similar to recently celebrated autobiographies or projects that are routed through Africa, like Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father, the story of African estrangement and ultimate reconciliation were relatable enough to be consumed by mass audiences, but President’s Obama project and ultimate access to his Kenyan family are not easily replicable by the average African American reader.

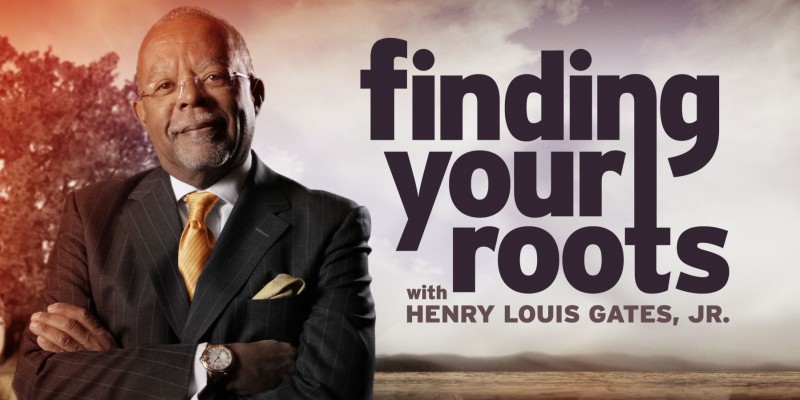

In that same vein, Henry Louis Gates’ award-winning “Finding Your Roots” PBS show highlights a means to subjectivity and deep historical and social recognition that is only available to the most elite and exceptional. Gates and the show’s staffers, seemingly with unlimited resources and time, scour records, find letters, and deploy experts to unearth the origins, contributions, and histories of these already celebrated peoples. As if we needed additional information about Oprah, Dave Chappelle, and Denzel Washington, Gates and his team reinscribes their mythic status by inserting them into this Roots structure. However, the goal of “Finding Your Roots” is not simply to create additional history of Dave Chappelle or Oprah, but the product is an easily consumable midrash on the Roots paradigm to further the narrative that this path is available to all who are willing to work hard enough to secure it. These celebrities feted and regaled by Henry Louis Gates have their histories and their roots, because they have tended to the project of neo-liberal capitalism and upward mobility. You too, can be saved from rootlessness, Gates and others seem to argue, if you follow in the path of rugged capitalism and use its bounty to access the best modern science and scholarship can offer.

While some might argue that DNA kits easily available to anyone with an email address and saliva have democratized this access to roots, I contend and again agree with Dr. Newton that the history and roots that these kits and their corporate sponsors offer are shallow and often offer inaccurate routes to a hazy Pan-African identity that could have been surmised without the $39 fee for entry. Moreover, Alondra Nelson in The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reconciliation, and Reparations after the Genome argues, that while DNA or DNA kits can provide us some answers, that neither science nor the double helix can alter a long history of being dehumanized or ignored by the modern project. Science alone, Nelson reminds, does not have the ability to radically change racial social norms and practices. In other words, neither Haley’s roots, the restorative possibilities of DNA, nor the knowledge that human origins began on the continent of Africa have radically shifted the dominant script of white supremacy in the modern era.

While Roots is a scripture that emerges in a particular moment in the history of the Black subject, it may prove less useful or adept at producing and protecting Black subjectivity for certain groups and during certain periods. I appreciate that the other secret of scriptures is that they require tending. Scriptures need tending or returning to. Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens reminds us that in order to get a fuller or better history of Black women’s contributions or to possibly discover scriptures that promote Black women’s wellness that she had to return or tend to their gardens. She dedicated her text to everyday women or as she says, “…it is to my mother-and all our mothers who were not famous-that I went in search of the secret of what has fed that muzzled and often mutilated, but vibrant, creative spirit that the black woman has inherited, and that pops out in wild and unlikely places to this day.” Newton gestures in this direction when he outlines the way that Roots is not just canonical, but it is scriptural because of its flexibility or porousness. Roots must be tended to. Roots, the text, becomes the means not only for a series of other genealogical re-imaginings that populate the last third of the twentieth century, but it is also produced a number of current cultural reboots. Even Haley, a good son of neo-liberal capitalism, retooled his Roots and reused it to tell the story of Queen, Haley’s paternal grandmother, and aligned himself with a new audience as he attempted to recover a version of Black women’s history. However, when Walker goes in search of her mother’s gardens, she imagines that there are some scriptures that must be radically altered and re-imagined to be fully seen.

Tending, in this regard, is not the work relegated to those on the periphery or those content to maintaining the status quo. Walker’s tending or returning to scripture is the work of overturning and pruning as to imagine new possibilities, recovery forgotten narratives, and to challenge the hegemonic readings that render some, if not most readers, invisible. Tending is transgressive and critical in the long work of womanists and the field of critical Africana Studies. Rather than a simple reboot or even a creative remix, certain types of tending understand its project as uprooting and repositioning the role of a text or an entire category. Thus, the final secret is that like the humans who are tending the scripture, scriptures, particularly Black ones, are living documents that will inevitably change and evolve as they provide safe harbors for radical possibilities and new futures for Black subjects.