“Who are you? What are you? Where is your soul or spirit? It’s not in that dead body…” – Dr. Robert White, Neurosurgeon and Bioethicist

Interdisciplinary pioneers of otherwise uncharted territory in the cognitive science of religion (CSR) are apt to ask some of the most provocative yet fundamental questions of human existence. These questions extend not only across the lifespan, but also into the realm of continued existence after death. A religious notion traversing cultural boundaries, reincarnation in particular and the cognitive processes underlying reincarnation beliefs are arguably foundational to understanding how people reason about existence and identity. Whether addressing how reincarnation is conceptualized or how to go about identifying the reincarnated, such questions are not only religious in nature, but experimental researchers are also beginning to explore these subjects and their associated cognitive processes through controlled empirical studies. Dr. Claire White of the Cognitive Science of Religion Lab at Cal State-Northridge asks exactly these questions in her research, which she summarizes in a recent interview with the Religious Studies Project.

Who are you?

Obviously, reincarnation invites inquiries around identity: What does it mean to be the same person or different people, either within or between lives? With the diversity of reincarnation beliefs in the world, there is no single consensus on the matter of identity, though converging streams exist.

Reincarnation beliefs are common throughout Buddhism and Hinduism as well as within several new age religious movements and among plenty of spiritual seekers in the west. Dr. C. White explains that other researchers of reincarnation have documented reincarnation beliefs in at least 30% of cultures, a figure that may actually be an underestimate on account of excluding ambiguous cases. Among those studying reincarnation, Dr. Tony Walter, Professor of Death Studies at the University of Bath and Dr. Helen Waterhouse, Visiting Honorary Associate in Religious Studies through the Open University have found that fewer people (of those surveyed in the UK) endorse the belief in reincarnation than those who find reincarnation plausible, which may include up to a quarter of all respondents [1].

In the interview, Dr. C. White points out this important distinction between 1) ontological commitment and 2) plausibility (on account of a belief being “cognitively sticky” or intriguing). Needless to say, significantly more people are willing to entertain the plausibility of reincarnation than are likely to wholeheartedly adopt reincarnation into their existing belief structure.

The prevalence of reincarnation beliefs cross-culturally and the appeal even to those who are not firm believers in reincarnation begs the question: why? Although there are several possible (and equally true) reasons for cultures and the individuals that comprise them to endorse reincarnation beliefs at some level, one possible function of reincarnation beliefs that deserves further attention is that they provide a means of circumventing one’s own mortality.

To confront the inevitability of one’s own death from the perspectives of nihilism and annihilationism in which death is viewed as the ultimate end raises the crisis of meaninglessness, which according to existential psychiatrist Dr. Irvin Yalom, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University, “stems from the dilemma of a meaning-seeking creature who is thrown into a universe that has no meaning” [2]. In a world where the only certainty is death, the sense of having no meaning in life conjures existential terror. According to Terror Management Theory (TMT), this existential terror results from the desire to live while being forced to acknowledge the reality of death [3], creating unavoidable conflict in the mind of the mortal. Importantly, empirical research on TMT indicates that mortality salience, or bringing to mind thoughts of one’s own death, leads to self-esteem striving, which involves pursuit of positive self-evaluations as a means of buffering against the terror and anxiety evoked by the uniquely human awareness of mortality [4].

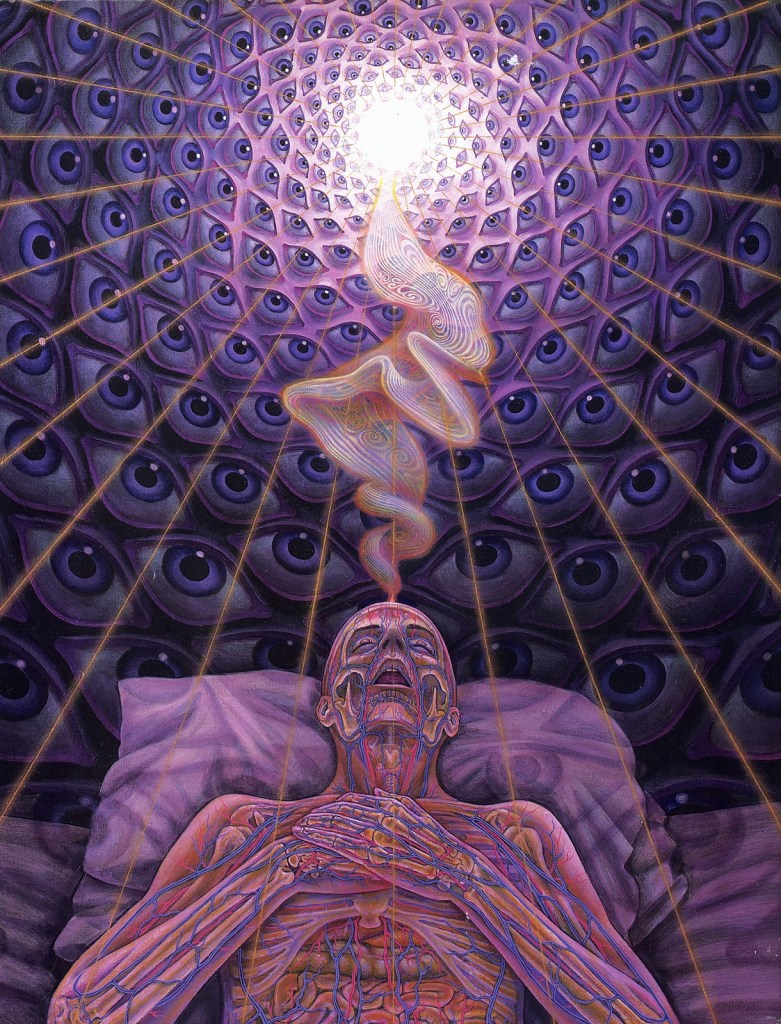

Both traditional and modern accounts of reincarnation presume continued existence and the preservation of some form of identity across lives in spite of physical death. The belief that death is not the end of existence (whether through adoption of reincarnation beliefs or some other form of afterlife) is understandably comforting to many. In fact, according to Yalom, desire for psychological “immortality” is the default response to existential anxiety. However, immortality, whether real or imagined as a defense mechanism against existential anxiety, requires some-thing to be immortal, some kind of enduring feature(s) to maintain uninterrupted identity.

What are you?

Two types of features are typically taken as evidence of identity, Dr. C. White explains:

- Physical marks

- Memories

When seeking to identify a reincarnated person, one strategy entails looking for specific physical marks, especially distinctive marks that are unlikely to belong to many people. Congenital traits are preferred and considered more reliable, since what is present from birth is less likely to change, indicating some degree of underlying stability.

The other commonly employed strategy is to match a reincarnate-candidate to the previous incarnation on the basis of memories, specifically episodic memories. Recognition, whether of another person or a particular object that should otherwise be unfamiliar, is trusted as an indication of identity during reincarnation searches. This is largely on account of the commonly accepted reasoning that memories represent continuity of self and communicate ownership.

Early research by the late Dr. Ian Stevenson, Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in the 1960s also attempted to address questions of reincarnation, albeit through an overwhelmingly anecdotal approach. Documenting cases of children whose memories and birthmarks matched those of the deceased, Dr. Stevenson accumulated several thousands of pages worth of photographic “evidence” of reincarnation. While groundbreaking for its time, Dr. Stevenson’s reincarnation research was unfortunately lacking in the empiricism and scientific rigor necessary to procure sufficient evidence for what he was purporting to prove. Nonetheless, his was among the first research to suggest that memories and physical marks can be transferred from one lifetime to another, thus serving as identifying traits among the reincarnated.

Where is your soul or spirit?

Buddhists are one religious group to directly confront the inevitability of death through meditation on mortality (which may involve visualization of corpses) while proposing rebirth as a means of [not-]self-preservation. The not-self part here is crucial, for reasons that Dr. C. White also mentions in her interview. She notes that in Buddhism there is no such thing as a permanent and enduring self, yet in Tibetan Buddhism in particular, the belief that an individual (e.g., His Holiness the Dalai Lama) reincarnates and can be identified based on recognition of objects belonging to their previous incarnation implies continuity of identity, or at least episodic memory. Dr. C. White suggests these reincarnation beliefs contradict the official teachings of the Buddhist tradition within which they are embedded.

As should be evident from any serious inquiry into the teachings of Buddhism, the Buddha rejected the existence of an enduring self that persists from life to life, like a soul or spirit, rendering the question “Where is your soul or spirit?” meaningless. Yet within Buddhism the notion of rebirth or reincarnation is widespread. A common question then raised by the uninitiated is, “if there’s no self, what gets reincarnated or reborn?” The question again becomes, “Who are you? What are you? Where is your soul or spirit? It’s not in that dead body…” Focus inevitably returns to that dead body… What once animated it and gave it life that is lacking in death?

As for the Buddha’s response, he discouraged needless speculation on the matter, deeming it unnecessary to the cessation of suffering [5]. Yet few find this silence satisfactory. Probing the annals of Buddhist philosophy, one finds that several schools of Buddhism purport that some subtle level of selfless consciousness is the culprit. Whether it is the bhavanga-sota/bhavanga-citta referenced by commentarial sources in Theravada Buddhism or the alaya-vijnana of Mahayana Buddhism, some form of sub-conscious life-continuum yokes together past, present, and future.

It’s not in that dead body.

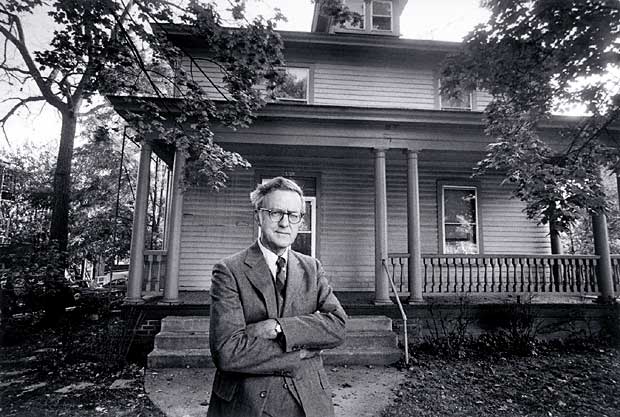

The other Dr. White quoted at the beginning of this piece, while never explicitly endorsing reincarnation beliefs, nonetheless raised several questions regarding identity that called upon both science and religion. Pivotal in the field of neurosurgery, the late Dr. Robert White, Professor of Neurological Surgery at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine until his death in 2010, is best known as a prominent head transplant surgeon, operating on several species ranging from dogs to monkeys. Obviously concerned about the ethical dimensions of his bizarre operations, throughout his career, “Dr. Frankenstein,” as he is otherwise called, often questioned his own practices as a surgeon from a critically bioethical perspective. Dr. Robert White proposed that the brain (which he believed was responsible for housing the soul) plays a central role in identity preservation. In fact, he is quoted in Scene Magazine: “I believe the brain tissue is the physical repository for the human soul.” He is also quoted in Scene Magazine, remarking “We discovered that you can keep a human brain going without any circulation…It’s dead for all practical purpose – for over an hour – then bring it back to life. If you want something that’s a little bit science fiction, that is it, man, that is it!”

As far as what happens to “that dead body” once “the not-self” uninhabits it, that is a question no scientist can sufficiently answer, as its metaphysical assumptions lie outside the purview of physicalist science and cannot be encapsulated by any intellectual system aiming to quantify qualia. Understanding what the self is and is not, and that even conceiving of “the not-self” is problematic in its reification of substanceless phenomena, seem to take precedence yet pose obstacles to CSR. Yet with emerging interdisciplinary research within CSR, the reasoning processes behind these notions of identity, existence, and continuity can at least be illuminated, even if the metaphysics remain unscathed.

Footnotes

[2] Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

[3] Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. Public Self and Private Self, 189-212.

[4] Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435-468.