In the podcast episode on “Following the Objects: Seeing Religion in Egypt and Syria“ with Richard McGregor I find many aspects of my own research and its process. The – as I understand – rather “accidental“ change of direction towards the object. The many surprises along the trails, roads, and boulevards taken in order to track down the objects of choice. The necessity to give “aesthetics“ back its full dimension beyond notions of beauty. The struggle with stubborn Islamic Art History vocabulary and language deficiencies in general.

Let me focus on one of the terms that Richard McGregor thankfully came up with, in order to bring these strands together anew through the perspective of my “objects that resist“ (RM 13:11). This uncommon quality on the long list of attributes we give to objects brings together all the aspects that I just mentioned—aspects that describe well how Islamic Studies research can take new shapes when in dialogue with material culture.

Instead of further working out details of theories of the object-human-relation from, let’s say, Martin Heidegger to Bruno Latour to Jane Bennett, the format of the response allows me to jump back into my own stream of thing-exploration once more. That stream opened up when I needed to follow “my objects“ in order to shed light on Islamisation in Syria (2000-2011) from a different perspective. I “accidentally“ and happily decided on commodities and their aesthetics. Looking back, no other method would have been suitable, neither for the subject nor for me as a researcher. I started the process of seeing, listening and understanding with the vast world of talismans: the biggest group of commodities with an Islamic connotation. So please follow me on a little digression, the same I had to take.

Talismans “kind of magically” (RM 5:41) brought me to non-academic literature and German peculiarities when it comes to material culture. There is an expression in German language going back to a famous 19th c. novel by the unsuccessful philosopher and aesthetic but all the more successful writer Friedrich Theodor Vischer that has become proverbial: “The cussedness of the (inanimate) object” (Die Tücke des Objekts). It describes the experience that things seem to lead a life of their own and sometimes put a spoke in our wheel. It describes the experience of things we mean – and believe – to operate but then realize that it is us who are being handled, who are being determined by the realities things create (tellingly, in German language we “serve” a machine when we operate it): Tools fall apart when we need them most. Laces produce knots when we are on the run. Televisions fail just during the finals. Throughout 19th and 20th c. German literature we find examples of objects that seem to have some kind of power and life of their own. Animate objects. Most parts of society tried to frame any kind of fetish-belief as “savage”, pathological, the Other. Hence, literature and arts became a playground for the “non-rational”, “non-modern” perspective on objects. In his story “The Cares of a Family Man“ (1917), Franz Kafka describes a thing – wooden, with many threads wrapped around, small and yet complex in shape – that seems to be beyond all known categories and uses. Reader and “family man“ follow it on its ways throughout the house:

“He lurks by turns in the garret, the stairway, the lobbies, the entrance hall. Often for months on end he is not to be seen; then he has presumably moved into other houses; but he always comes faithfully back to our house again (…) Many a time when you go out of the door and he happens just to be leaning directly beneath you against the banisters you feel inclined to speak to him. Of course, you put no difficult questions to him, you treat him – he is so diminutive that you cannot help it – rather like a child. ‘Well, what’s your name?’ you ask him. ‘Odradek,’ he says. ‘And where do you live?’ ‘No fixed abode,’ he says and laughs; but it is only the kind of laughter that has no lungs behind it. It sounds rather like the rustling of fallen leaves. And that is usually the end of the conversation.”

Franz Kafka, “The Cares of a Family Man” (1917)

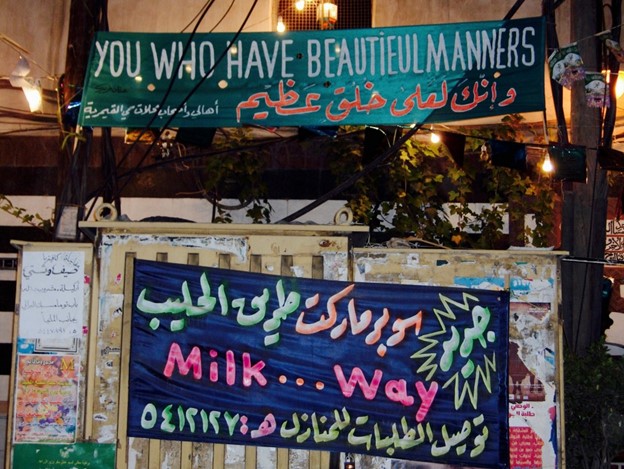

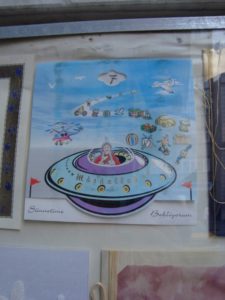

Unsatisfactory dialogues like that happen when a head loaded with ideas and concepts of Islam and Muslim practices encounters unexpected things, things in an unexpected use or place. This head would like to finally situate the object but that irritating thing just keeps moving. It could be a prayer rug that has left its place on the ground or shelf (or even museum!) and has become a simple awning to keep away the sun. It could be a talisman to ward off the Evil Eye that has the blue color and shape of the common Turkish Nazar but is decorated not with the usual abstract eye but with “Tom and Jerry” instead. It could be an Islamic gown decorated with not fewer than three international brand logos. It could be a greeting card for circumcision celebrations where the highly decorated boy is displayed in a UFO. “Häää?,” I remember my German inner voice saying.

To keep this conversation with the Resisting Object alive, new listening skills have to be developed. This is where the “aesthetic communication“ (RM 12:21) needs to set in. Though, when it comes to seemingly banal objects like commodities, Islamicists’ listening often stops. Materials that do not belong to the canon of Islamic Arts are excluded far too often from academic dialogue with the object (rather monologue though, many times). The same applies to mass-produced items.

If I understand Richard McGregor correctly, he aims for a new language, and it has yet to be discovered where that is to be found or learnt. Without question, the body has come into play with its own knowledge of how body and thing interact. Of how an Abaya dress made from polyester sticks to the skin and develops a smell. Of how prayer beads made from wood, glass, ceramics, tin or plastic sound and feel when slipping through the fingers. Of how a finger-long Zulfikar sword worn around the neck gives weight to every movement.

But the body alone cannot deal with the language problem that we have.

I plead for a daring exploration of words and categories that helps us to go beyond museal descriptions supplying era, material and a single use. One major problem on the way is those notions of beauty in the term “aesthetics.” They hinder communication at eye level. So we need to get rid of them for a bit. If contemporary Islamic and Muslim things and their aesthetics are shaped by shimmering crystal, neon light, and gold imitations then these have to be materials and aesthetics we communicate and think with. Hence, they do shape Muslim perception and life on a daily basis. And they will lead us back to Islamic concepts and to their expression in time. To the meaning of al-nur, the light, to visions of paradisical gold and to an Islamic canon of materials to be neglected: in this world.

I wish McGregor’s book had been out when I wrote mine. It would have made the long process less lonesome. Here is a very much incomplete list of works and authors I am indebted to:

Böhme, Hartmut. 2014. Fetishism and Culture. A Different Theory of Modernity. Berlin & Boston: de Gruyter.

Ingold, Tim. 2010.The Textility of Making. In: Cambridge Journal of Economics 34: 91–102.

Naef, Sylvia. 2000. Einige Überlegungen zur Unterscheidung zwischen sakralem und profanem Raum im Islam. In Religiöse Kartographie. Organisation, Darstellung und Symbolik des Raumes in religiösen Symbolsystemen edited by F. Stolz/D. Pezzoli-Oligiati. Berlin: 289–307.

Pinto, Paulo. 2007. Pilgrimage, Commodities, and Religious Objectification. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27: 109-125.

Starrett, Gregory. 1995. The Political Economy of Religious Commodities in Cairo. In: American Anthropologist 97:. 51–68.