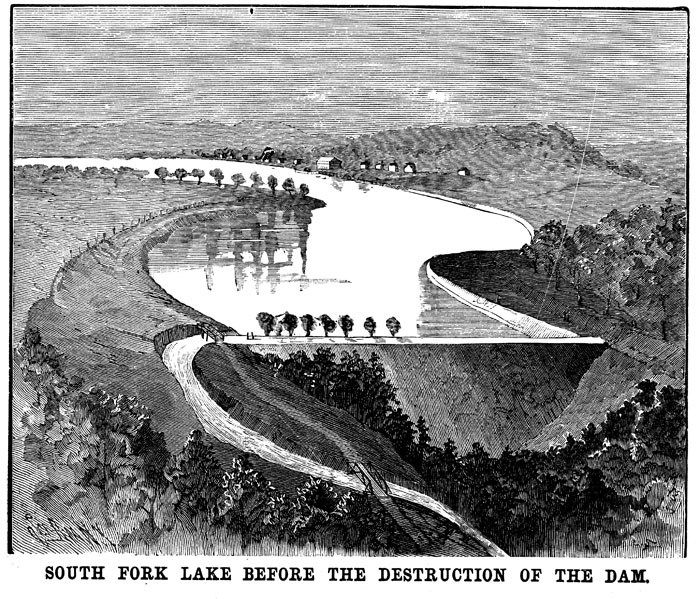

The South Fork Dam once stood high above the city of Johnstown Pennsylvania, erected to supply water to one of the many canal systems that made up the early American interstate trade route. Purchased by the South Fork Hunting and Fishing club in 1881, the massive body of water behind the dam, Lake Conemaugh, was made part of an exclusive mountain resort for the wealthy from nearby Pittsburgh. Over the next eight years frequent inspections found the South Fork Dam to have many foundational flaws, as well as a number of recurring surface cracks. With gilded aesthetics in mind these cracks were mended by rudimentary patchwork, a temporary slathering of mud and straw. On the rainy afternoon of May 31st, 1889 the dam melted under the pressure of the swelling lake, releasing a surging wall of water onto the city below. By the time the water receded 2,209 people had perished in one of the worst “natural” disasters in US history.

As anecdotes go, this is a pretty good one. The impudence of the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club contributed to the idea that by solving surface issues with a little patchwork the real problem at the foundation would equally be resolved. In the field of academia we come across this sort of logic quite regularly; more so, it seems, in the category of religious studies.

Sean Bean as Odysseus in the movie ‘Troy’It seems fair to say that ours is a rather dangerous vocation, not dangerous in the way a dam keeper’s job might be dangerous on an afternoon of heavy rain, but dangerous in that we bravely tread the waters of humanity’s inner-most sacred beliefs and practices. This is not a gentle sea by any means. Tempests rise up unexpectedly, detouring our crossing with tangential distractions—much like those which plagued that long adrift Greek hero, Odysseus. Like him, we too seem impassioned to return to something genuine and practical, longing to once again stand on familiar soil; and we are ever creative in our ways of doing so.

Recently, Professor Jay Demerath took up such a challenge, which formed the basis for his interview with Chris Cotter. Promoting the replacement of the ambiguous term “religion” with the functional term “sacred,” Demerath’s novel approach at interpreting that which stands out against the profane or secular comes with two critical issues: definition and application.

Definition

Demerath originally proposed this turn from “religion” to “sacred” in his deliberately misquoted “Varieties of Sacred Experience,” nominally linking his amended term with the foundations of religious studies in William James’ “Varieties of Religious Experience.” This calculated revision brings Demerath’s proposition into the context of debate between experience and belief as designated by the modern ambiguity of “religion” and his novelized sobriquet, “sacred.” As he states, “religion is just one among many possible sources of the sacred,” (Demerath 2000) and that the ambiguity which anchors itself to the definition of religion can easily be weighed by defining it substantively, while interpreting its consequences, “the sacred,” functionally. This is a methodological proposition which focuses not on the encompassing importance of “religion” but rather on what it is that individuals—or groups—take to be “sacred.” By divesting religion and sacred between substantive and functionalist, assigning “religion” to the “category of activity” and seeing the “sacred” as a “statement of function” both terms seem to work in their application

This is further demonstrated in his polythetic method of deciphering that which individuals and social groups set apart as being “sacred.” In the interview, when asked how sociologists navigate the ambiguity of what is sacred or not, he suggests a sort of polythetic taxonomy when it comes to deciphering what is sacred to the people under examination. By developing a “kind of a checklist of behaviors that are associated with what might be a sacred commitment,” such as is found in certain categorical methodologies (Saler 1993, Smith 1996, Smart 1997), he believes we can properly decipher what “people do, what they don’t do, what they believe, what they don’t believe, what they observe and don’t observe.” Furthermore, this alludes to a stipulation of terms, rather than a dependence on real definitions (Baird 1971). Both techniques reveal a method which assists us in accessing the “priority” of the religious person’s “commitments, the commitments in their life, and the convictions in their life.” (Demerath 2012).

However, Demerath is also navigating very dangerous waters here, steering between narrow straights where on one side awaits the swirling temptress of a definition of religion, and on the other the horrifically multifaceted monster of misapplication. For example, if removed from his sociological context, how does his term “sacred” differ from that of “religious?” One of the advantages with stipulative definitions is that they must be anchored to a particular study, the borders of which Demerath’s proposition seems to push against. Consider if we categorically formed a stipulative interpretation of the traditional term “religious” as pertaining to the consequences of the practitioner’s “religion,” would we not be able to equally balance out the ambiguity found in “religion?” Would using a stipulated interpretation of “religious” as the function of a person acting under the substantive form of “religion” not be the same? While Demerath responds to a similar question in the interview by legitimating his use of the “sacred” as something that does not need to transcend our world to some other-worldly deity, he is limiting himself to a “definition” of religion devoted to a transcendental relationship between man and deity. This seems, again, a difference between “religion” and “religious” as equally as it pertains to the difference between “religion” and the “sacred.” This is an issue of definition and application. Where his turn from the sociology of religion to the sociology of the sacred succeeds and fails is within this issue. By pushing against these borders his stipulation begins to sink into the periphery of real definition. Fortunately he saves himself with the life-raft of an applicative example.

Application

The decision of United States vs. Seeger is about as close to a “definition” of religion the United States Supreme Court is legally allowed to make. The disestablishment clause of the 1st Amendment—Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion—is a collection of ten words which make the United States exceptional to religiously established nations such as England and Scotland. It also creates quite the conundrum when cases like these come to the Court’s attention. The Seeger case did not occur ex nihilo, but was rather the result of the decisions in Everson vs. Board and Torcaso vs. Watkins, steps made by the court over twenty years of social and political change in a country seeking an umbrellic identity between the end of World War II and the turbulent second half of a decade that saw the assassination of John F. Kennedy at one end, and the resignation of Richard M. Nixon at the other.

This brief circumnavigation speaks directly to Demerath’s application of the term sacred. When seen through the lens of American legal amendments, wherein the “belief in and devotion to goodness and virtue for their own sakes,” and a religious “faith in a purely ethical creed” amounts to a “a sincere and meaningful belief occupying in the life of its possessor a place parallel to that filled by God,” what is construed as “sacred,” the “ultimate concern” may seem counter to even the most liberal applications of “religion.” (U.S. vs. Seeger) By amending the qualifications of article 6(j) of the Universal Military Training and Service Act to accommodate Daniel Seeger’s philosophical views, the function of Tillich’s substantive definition, as accepted by the Court as a standard by which to measure the religiousness of the individual, “religious” and “sacred” become stipulative suggestions, pliable by what might justify a sacred belief. Thus, in a nation devoted to a sense of individual sacralization, the nation of Sheilaism (Bellah et al.), Demerath’s reassignment of transcendental “religion” with “sacred” seems justified.

Conclusion

While the legitimation of his using “sacred” rather than “religion” seems justified in the above sample, it still seems a patchwork fix rather than a foundational repair. It should be said, though, that this is not so much a critique of Demerath’s thesis, but of the idea in promoting a new term as the replacement of an old one. Perhaps this is due to the definitive style it seems to imply at the suggestion of “sacred studies” rather than “religious studies.” New terms are not always the best way to fix a foundational issue such as the ambiguity of “religion” in a global context. Instead, we would benefit far greater by digging up and unpacking what we mean by terms when studying the practitioners who make them sacred in specific contexts. The stipulation of an established, utilitarian term like “religious” to mean the actions of individuals seeking what they deem foundationally sacred relieves the pressures of ambiguity just as equally as “sacred,” especially because of its relationship and differentiation from “religion.” Perhaps a good argument against Demerath’s contextual use of “sacred” might be a change from the “sociology of religion” to the “sociology of the religious.”

Definitions of religion seem the ever-widening Charybdis in the field of religious studies—in all its forms. In our contemporary world we tend to find ourselves more absent-mindedly sailing toward the yawning mouth of that swirling vortex known as “a definition of religion.” We need to be cautious with the application of new terms. We seem too often prone to kneejerk patchwork, slathering layer upon layer of temporary fixes, either impudent in our knowledge of foundational issues, or victims of deep denial. We long to resolve ambiguity by applying more ambiguity, when we should just dig up the foundation and rebuild. These waters are dangerous, and without precaution we appear more and more drawn into the riptide of circular academia where, once swallowed up, we run the risk of drowning in a sea of uncertainty.

References and Suggested Reading

- Robert D. Baird. Category Formations and the History of Religions. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1991.

- Robert N. Bellah. Beyond Belief: Essays on Religion in a Post-Traditionalist World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Robert N. Bellah, et al. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- James L. Cox. “Afterword: Separating Religion from the ‘Sacred:’ Methodological Agnosticism and the Future of Religious Studies” in Steven J. Sutcliffe. Religion: Empirical Studies. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Jay Demerath. “The Varieties of Sacred Experience: Finding the Sacred in a Secular Grove” in the Journal for theScientific Study of Religion, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2000.

- ———. “Defining Religion and Modifying Religious “Bodies:” Secularizing the Sacred and Sacralizing the Secular” in Phil Zuckerman, ed. Atheism and Secularity: Volume 1: Issues, Concepts, and Definitions. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2010.

- ———. Religious Studies Project Interview with Jay Demerath on Substantive Religion and the Functionalist Sacred (12 March 2012).

- David McCullough. The Johnstown Flood: The Incredible Story Behind One of the Most Devastating “Natural” Disasters America has Ever Known. NewYork: Touchstone, 1987.

- Ethan Gjerset Quillen, 2011. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion. MA Thesis, Baylor University, Waco, Texas.

- Bensor Saler. Conceptualizing Religion: Immanent Anthropologists, Transcendent Natives, and Unbounded Categories. New York: E.J. Brill, 1993.

- Ninian Smart. Dimensions of the Sacred: Anatomy of the World’s Beliefs. New York: Fontana Press, 1997.

- Jonathan Z. Smith “A Matter of Class: Taxonomies of Religion” in The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 89, No. 4, 1996.

- Terence Thomas. “‘The Sacred’ as a Viable Concept in the Contemporary Study of Religions” in Steven J. Sutcliffe. Religion: Empirical Studies. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947)

- Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961)

- United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965)

- Welsh v. United States, 398 U.S. 333 (1970)